Today we’re publishing a guest post from Roger Atwood, author of “Stealing History: Tomb Raiders, Smugglers and the Looting of the Ancient World.” We reached out to Roger for his thoughts when we heard about an exhibition of suspect pre-Colombian material at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore. Atwood has written extensively about looting in Latin America, and took a recent trip to the Walters to see the collection. Here is what he found.

Today we’re publishing a guest post from Roger Atwood, author of “Stealing History: Tomb Raiders, Smugglers and the Looting of the Ancient World.” We reached out to Roger for his thoughts when we heard about an exhibition of suspect pre-Colombian material at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore. Atwood has written extensively about looting in Latin America, and took a recent trip to the Walters to see the collection. Here is what he found.

The Walters Art Museum in Baltimore has mounted a show of ancient artifacts from Latin America that belong, or once belonged, to the collector John Bourne. According to the show’s catalogue, Bourne has already given some of the pieces to the museum while others have been promised, a long, gradual donation that maximizes the donor’s tax deduction. Aside from a few likely fakes, whose presence the Walters candidly admits, the objects all date from before the arrival of Europeans in 1492.

The collection has a long and checkered history. Bourne originally intended to give it, or at least part of it, to the Museum of New Mexico’s Palace of the Governors unit in Santa Fe, which, in fact, displayed it for several years after 1997. The collection brought the Palace of the Governors some problems, to put it mildly. Four objects in the collection were seized by the FBI in 1998 and held for nearly two years, pending probes into allegations that the pieces were looted and smuggled out of Peru. The investigation ultimately fizzled, leading to no charges and the return of the pieces. But the Museum of New Mexico got some nasty publicity from that case, and one can only assume the Walters and its lawyers were fully cognizant of the risks of a repeat of it before accepting this dubious gift. I tell the story of the Bourne case in detail in my 2004 book Stealing History: Tomb Raiders, Smugglers, and the Looting of the Ancient World, based on interviews and documents acquired through the Freedom of Information Act.

A couple of weeks ago I took a train to the handsome city of Baltimore and saw the Bourne collection in its new home. It’s a revealing show with some lovely artifacts, including some I don’t remember seeing in Santa Fe. The painted Nasca stirrup bottles (right), masterpieces of design and economy dating from about 500 CE, alone were worth the trip.

A couple of weeks ago I took a train to the handsome city of Baltimore and saw the Bourne collection in its new home. It’s a revealing show with some lovely artifacts, including some I don’t remember seeing in Santa Fe. The painted Nasca stirrup bottles (right), masterpieces of design and economy dating from about 500 CE, alone were worth the trip.

Yet I came away thinking that, perhaps without realizing it, the organizers have given an object lesson in the dangers of collecting antiquities that have no record of archaeological excavation. What I wrote in Stealing History – that “not a single piece on display” in the Bourne collection “gives a specific provenance, archaeological history or other sign it emerged from any place but a looter’s pit” – remains true but needs some amending.

First, there are the fakes. To its credit, the Walters is completely up front about the fact that some pieces in the Bourne collection are probably not what they claim to be. “[T]he atypical imagery of these objects calls into question their authenticity,” says the wall label next to a pair of Maya eccentric flints. It adds, helpfully, that tests are inconclusive “because modern replicas are made using the same kinds of tools and techniques as well as the same sources of flint” as the real ones. So, in this case, we’re learning more about technique for making fakes than about Maya flints.

First, there are the fakes. To its credit, the Walters is completely up front about the fact that some pieces in the Bourne collection are probably not what they claim to be. “[T]he atypical imagery of these objects calls into question their authenticity,” says the wall label next to a pair of Maya eccentric flints. It adds, helpfully, that tests are inconclusive “because modern replicas are made using the same kinds of tools and techniques as well as the same sources of flint” as the real ones. So, in this case, we’re learning more about technique for making fakes than about Maya flints.

Another sculpture looks like a bad pastiche of old and new, or, as the wall panel says, a “modern assembly of a variety of ancient parts.” Meant to look Moche, the piece shows a wooden, crouching warrior of ungainly proportions, with a clamshell perched on its head like a fez and a backflap on its lower back that seems to have been made for a much smaller object. “Together, the C-14 [radiocarbon dating] and iconographic data suggest that the piece – in its current state – postdates Moche culture by at least 700 years,” says the show’s catalogue. The operative phrase there is “at least,” for the piece has a funny, cinematic kind of look, like a prop from “The Curse of the Andes”.

What do fakes have to do with the problem of looting? Fakes and unprovenanced, authentic antiquities often turn up together in collections because neither was found through the transparent process of archaeological excavation. They flock together. Collectors might think their connoisseurship protects them from fakes, but they get hoodwinked all the time. This is not a sign of denseness or gullibility, necessarily; it just comes with the territory if you’re in the business of acquiring undocumented antiquities. If the Getty, with all its experts and budget, could buy a dubious piece like the Kouros, then what hope is there for a single collector such as John Bourne, no matter what the credentials of the people advising him?

What do fakes have to do with the problem of looting? Fakes and unprovenanced, authentic antiquities often turn up together in collections because neither was found through the transparent process of archaeological excavation. They flock together. Collectors might think their connoisseurship protects them from fakes, but they get hoodwinked all the time. This is not a sign of denseness or gullibility, necessarily; it just comes with the territory if you’re in the business of acquiring undocumented antiquities. If the Getty, with all its experts and budget, could buy a dubious piece like the Kouros, then what hope is there for a single collector such as John Bourne, no matter what the credentials of the people advising him?

The Walters is more coy on the implications of all this. Has the collector gained a tax benefit for the donation of what are quite possibly, if the Walters’ analysis is correct, worthless fakes? Why is it even showing them? The show constantly refers to authentication and laboratory analysis on the pieces; indeed, it’s one of the main themes of the exhibit. One piece, a Zapotec pottery figure actually has a copy of its thermoluminescence analysis report right on the wall, indicating the piece dates from 450 to 800 CE. Wall texts and the catalogue go on about CT scans and minute studies of chemical compositions.

I spoke on the phone with the director of the Walters, Gary Vikan, who said that the museum decided to go ahead and show what its conservators believed to be fakes because “there is a value in being candid and open about our own research.” He added, “our business is to gather and share knowledge, not to vindicate” a collector’s decisions. Two conservators worked full-time for two-and-a-half years analyzing the pieces, he said.

I spoke on the phone with the director of the Walters, Gary Vikan, who said that the museum decided to go ahead and show what its conservators believed to be fakes because “there is a value in being candid and open about our own research.” He added, “our business is to gather and share knowledge, not to vindicate” a collector’s decisions. Two conservators worked full-time for two-and-a-half years analyzing the pieces, he said.

To the viewer, all this research could signal that the Walters has doubts about the larger integrity of the collection. But it also suggests the museum is trying to compensate for the lack of any archaeological information about the pieces by running them through gauntlets of laboratory tests. It’s as if the museum is trying to scratch its way to some information – any information – about pieces that are so patently lacking any hard archaeological data.

And that leads me to the second problem associated with undocumented artifacts that this exhibit so richly demonstrates: the lack of information. For all the museum’s months of laboratory work, we know strikingly little about where these pieces came from, in what context they were found, and what function or meaning they had. This is because they were, presumably, all purchased from the cast of looters, dealers and assorted hoodlums that make up the supply end of the Latin American antiquities market. Whatever information those sellers claim to have on the origin of the artifacts they sell is usually conjecture or lies.

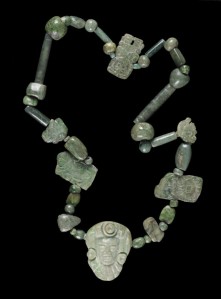

An earthenware crocodile effigy claimed to be from Costa Rica is said to date from 500 to 1350 CE, an absurdly wide spread that stratigraphic data or radiocarbon materials found in proper excavation could narrow down to decades. A Mayan jadeite pendant (left) dates from “250 to 450 CE” and could come from Guatemala, Belize, Mexico or Honduras, says the catalogue. In other words, from two centuries and any one of hundreds of sites over four countries. It’s a nice piece, but how helpful is that? True, it is difficult for a private collector to buy archaeologically excavated material, since it rarely comes on the market. But a museum of the Walters’ caliber could certainly arrange loans of properly excavated pieces if wants to show pre-Columbian antiquities.

An earthenware crocodile effigy claimed to be from Costa Rica is said to date from 500 to 1350 CE, an absurdly wide spread that stratigraphic data or radiocarbon materials found in proper excavation could narrow down to decades. A Mayan jadeite pendant (left) dates from “250 to 450 CE” and could come from Guatemala, Belize, Mexico or Honduras, says the catalogue. In other words, from two centuries and any one of hundreds of sites over four countries. It’s a nice piece, but how helpful is that? True, it is difficult for a private collector to buy archaeologically excavated material, since it rarely comes on the market. But a museum of the Walters’ caliber could certainly arrange loans of properly excavated pieces if wants to show pre-Columbian antiquities.

The show takes pains to stress that Bourne purchased many artifacts on trips to Latin American hinterlands starting in the 1940s, before most current rules on removing and selling cultural property were in effect. The catalogue describes Hiram Bingham-style adventures, Bourne cutting through forest to reach the lost city of Bonampak and finding artifacts in situ. These accounts are entertaining and I don’t doubt their authenticity, but other facts make you wonder if he had other sources. Bourne himself told the FBI in 1998 that he bought merchandise from the late Ben Johnson, a notorious Los Angeles dealer in high-end pillage whose dealings were exposed in the Sipán trial of 1989.

What little information we’re given on the origin of the Bourne pieces amounts to a roll call of the most pitilessly looted parts of Latin America: the north coast of Peru, the Petén lowlands of Guatemala, rural Veracruz. Commercial looters erased incalculable amounts of archaeological data and a valuable economic resource to gather prizes for middlemen and collectors. It’s a story of exploitation and greed that is still rarely acknowledged by big collecting museums.

A clear example of that destructive cycle – collectors buy loot, looters destroy sites to get more loot to sell, over and over – was the pillage at Sipán in northern Peru in 1987. Before the Getty’s Aphrodite, before the Marion True trial, the case of Sipán showed everyone the power of the antiquities trade to consume heritage. That case led to the 1990 emergency ban on the import of a long list of types of Peruvian antiquities, arguably the most important step by the federal government to tackle the illicit trade up to that time, and, later, a bilateral agreement between Peru and the United States imposing broad import restrictions that remains in effect today. (By way of disclosure, I should say that I spoke in favor of a five-year renewal of that agreement before the State Department’s Cultural Property Advisory Committee in 2007.)

The Bourne collection (now the Walters collection) includes a piece widely attributed to Sipán, a golden belt rattle (left) [Note: An earlier version of this post had an incorrect image. The mistake was ours, not Atwood’s.] It wasn’t on display when I visited Baltimore but it appears in the catalogue, which calls the piece “Moche style, North Coast, Peru.” The Sipán tomb was looted by the Bernal brothers in February 1987. Its fabulous artifacts spread quickly through the elite antiquities racket before police fenced off the site and allowed archaeologists to excavate it. They found two more, undisturbed tombs that have enriched our understanding of pre-Columbian society.

The Bourne collection (now the Walters collection) includes a piece widely attributed to Sipán, a golden belt rattle (left) [Note: An earlier version of this post had an incorrect image. The mistake was ours, not Atwood’s.] It wasn’t on display when I visited Baltimore but it appears in the catalogue, which calls the piece “Moche style, North Coast, Peru.” The Sipán tomb was looted by the Bernal brothers in February 1987. Its fabulous artifacts spread quickly through the elite antiquities racket before police fenced off the site and allowed archaeologists to excavate it. They found two more, undisturbed tombs that have enriched our understanding of pre-Columbian society.

The word “style” after Moche is a wink-wink that the Walters is not sure of the piece’s authenticity, as Vikan pointed out to me. I spoke with one of the museum’s conservators, Jessica Arista, who said the surface of the belt rattle showed marks from metal tools that did not exist in ancient Peru. “There are a lot of modern polishing marks,” she said. Also, said Arista, the metal itself looked too fresh to be ancient and a corrosive pigment seems to have been applied to it, possibly with the intention of making it look older. A sample from the piece was detached and sent to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston for analysis, she said. The piece was found to be 72 percent gold, 13 percent silver and 10 percent copper, figures similar to those found in authentic pieces, she said. (The catalogue gave slightly different numbers: 86.6 percent gold, five percent silver and 8.4 percent copper.) But the interior of the metal lacked the leaching and compositional variation that you would expect from a truly ancient piece, she said. Also, the microscopically thin gilding that you would see on the surface seems to be missing.

Still, the information is not conclusive, said Arista. The museum would need detailed comparisons with authentic Sipán pieces to give a more definitive answer on the piece’s authenticity. The Walters has not made contact with the Sipán museum in Lambayeque, Peru to arrange such a comparison, she said.

I mentioned to her that many Sipán pieces, including the backflap seized by the FBI in Philadelphia in 1997, had been soaked and scrubbed with Brillo pads while in the hands of looters and smugglers. This, I suggested, could account for the modern tool marks and the metal’s shiny appearance (which I’d also noticed in Santa Fe.) Perhaps, she said, but the metal’s inner composition, not just the surface, raises red flags about the piece’s authenticity.

The belt rattle was one of four from the Bourne collection seized by the FBI in 1998. (Another, a golden monkey head looted from a nearby site called La Mina around 1988, was restituted to Peru last year, with the cooperation of the Palace of the Governors. A pair of Moche earflares, seen at right, also seized by the FBI remain on display at the Walters. ) While the artifacts were held by the FBI, the Peruvian archaeologist who excavated Sipán, Walter Alva, went to Santa Fe and examined the belt ornament. If he had any doubts about its authenticity, he never raised them with me or the FBI. Alva doubted the authenticity of other Peruvian pieces in the Bourne group, but not that one. In Stealing History, I quote Christopher Donnan of UCLA, an expert on Moche iconography, as saying he also believed it an ancient Sipán artifact. I’ve never heard an authority on Moche archaeology say anything different.

The belt rattle was one of four from the Bourne collection seized by the FBI in 1998. (Another, a golden monkey head looted from a nearby site called La Mina around 1988, was restituted to Peru last year, with the cooperation of the Palace of the Governors. A pair of Moche earflares, seen at right, also seized by the FBI remain on display at the Walters. ) While the artifacts were held by the FBI, the Peruvian archaeologist who excavated Sipán, Walter Alva, went to Santa Fe and examined the belt ornament. If he had any doubts about its authenticity, he never raised them with me or the FBI. Alva doubted the authenticity of other Peruvian pieces in the Bourne group, but not that one. In Stealing History, I quote Christopher Donnan of UCLA, an expert on Moche iconography, as saying he also believed it an ancient Sipán artifact. I’ve never heard an authority on Moche archaeology say anything different.

So if the Sipán belt rattle turns out to be a fake – well, there are some very good forgers out there, and kudos to the Walters’ conservation team for exposing it.

But if it’s not, then the Walters will have some explaining to do. Its presence at the Walters would make a mockery of the museum’s policy (stated by Vikan here at minute 18) of not acquiring pieces that do not have a clear chain of ownership from before the UNESCO agreement of 1970. Vikan says in the catalogue that the museum will “promptly and openly respond to any claims for repatriation … from possible source countries.” Indeed, in a sign of transparency, the Walters has posted the collection – including the now-suspect Sipán belt rattle – on the American Association of Museum Directors’ Object Registry of antiquities acquired since 2008 that lack clear provenance dating back to 1970.

But why wait until source countries make repatriation claims? You wonder what other controversies over title might lurk behind the Bourne collection. This would be a good opportunity for a major American museum to recognize proactively a source country’s title to dubious objects, rather than make Peru or Guatemala jump through hoops — or wait for the storm as the Met did with the Euphronios krater, today recognized as property of the government of Italy. Museums badly need to get the provenance problem past them and institute policies they can live by, permanently and consistently. At its heart, the question is about more than ownership. It’s about accountability, a subject on which the Walters exhibit demonstrates how far museums have come. It also shows how far they have to go.

ROGER ATWOOD investigated the illicit antiquities trade in 2002-03 with a fellowship from the Alicia Patterson Foundation. His website is http://rogeratwood.com/

January 24th: The National Press Club.

January 24th: The National Press Club.