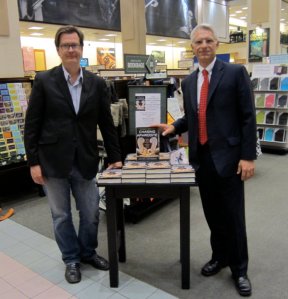

We’ve submitted the following response to Hugh Eakin’s review of Chasing Aphrodite, which was published in The New York Review of Books earlier this month. As you’ll see, we found the review flattering in places, but also curiously littered with contradictions. For those who don’t know him, Eakin covered the antiquities scandals for the New York Times and other publications.

Hugh Eakin’s review of our book Chasing Aphrodite: The Hunt for Looted Antiquities at the World’s Richest Museum (“What Went Wrong at the Getty,” NYROB June 27, 2011) was begrudgingly complimentary in several places, but also curiously littered with internal contradictions and a derisive tone that went unsupported by any argument of substance.

Hugh Eakin’s review of our book Chasing Aphrodite: The Hunt for Looted Antiquities at the World’s Richest Museum (“What Went Wrong at the Getty,” NYROB June 27, 2011) was begrudgingly complimentary in several places, but also curiously littered with internal contradictions and a derisive tone that went unsupported by any argument of substance.

The review opens with a straw man argument. Eakin claims our goal was “to debunk the notion that art museums might have some legitimate reason for collecting art from the ancient past.” This is false. As the book makes clear, we have no objection to museums collecting ancient art — legally. Our aim, clearly stated in the preface, was to show that museums’ laudable goal of preserving and protecting antiquities was undermined by their decades-long reliance on an illicit trade that destroys our knowledge of the ancient world.

Eakin claims we do not support our statement that, by fueling the black market, museums have destroyed more knowledge than they have preserved. On the contrary, we make that case time and again in what Eakin, in his next breath, calls our “almost overwhelmingly detailed account.” There is no better illustration of our case than the object at the center of the book, the Getty’s cult statue of “Aphrodite.” Looted from an archaeological site in Sicily in the late 1970s, the Getty bought it in 1988 despite clear signs it was illicit. Thanks to the pall of scandal that hung over the goddess, it was never subjected to serious scholarly study during its 22 years at the Getty, despite being, in the words of the Getty’s curator, “the single greatest piece of Classical sculpture in this country.” Like much of the ancient art in American museums, the Aphrodite was a mute object of beauty.

Indeed, as our book documents, Getty officials actively avoided knowledge of the statue’s origins, turning down several opportunities to learn more about its history and meaning. Soil found in the statue’s folds sat in vials unexamined for 19 years, despite the initial pleas of the head of the Getty conservation institute. True turned down an opportunity to view photos of the statue before its restoration, despite the possibility that they might clarify the goddess’ true identity. The Getty even refused to obtain missing fragments from the statue from the man they publicly claimed was its original owner. (The case of the Aphrodite is no anomaly, as the Met’s persistent refusal to allow a leading archaeologist to study that museum’s illicit Greek silver service showed.) How to explain this bizarre aversion to the truth at an organization whose mission is the “diffusion of knowledge”? The Getty was so intent on keeping this illicit beauty in Malibu that it was willing, time and again, to sacrifice the truth about her origins. Only after the Getty agreed to return the statue to Sicily, where it now resides, did it invite scholars to begin the arduous process of reconstructing that lost history. As if to underscore the museum’s history of obfuscations, many experts now believe the goddess represents Demeter or Persephone, not Aphrodite.

Indeed, as our book documents, Getty officials actively avoided knowledge of the statue’s origins, turning down several opportunities to learn more about its history and meaning. Soil found in the statue’s folds sat in vials unexamined for 19 years, despite the initial pleas of the head of the Getty conservation institute. True turned down an opportunity to view photos of the statue before its restoration, despite the possibility that they might clarify the goddess’ true identity. The Getty even refused to obtain missing fragments from the statue from the man they publicly claimed was its original owner. (The case of the Aphrodite is no anomaly, as the Met’s persistent refusal to allow a leading archaeologist to study that museum’s illicit Greek silver service showed.) How to explain this bizarre aversion to the truth at an organization whose mission is the “diffusion of knowledge”? The Getty was so intent on keeping this illicit beauty in Malibu that it was willing, time and again, to sacrifice the truth about her origins. Only after the Getty agreed to return the statue to Sicily, where it now resides, did it invite scholars to begin the arduous process of reconstructing that lost history. As if to underscore the museum’s history of obfuscations, many experts now believe the goddess represents Demeter or Persephone, not Aphrodite.

American museums have contributed important scholarship to the field with projects such as the Corpus Vasorum – a painstaking study of Greek vases advanced by curators at the Met, the Getty, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and elsewhere. But just as often, their public mission to educate has been undermined by their private lust for recently excavated objects. Sadly, there is no similarly detailed record of what was lost as a result. But to suggest, as Eakin does, that the damage done by looting is negligible compared with the scholarly good done by American museums requires some extraordinary contortions. One must also believe that every time a looter sticks a shovel in the ground, he “rescues” a museum-worthy antiquity like the Aphrodite and has no further need to ransack the archaeological site in question. In truth — as has been documented in books and articles going back to Clemency Coggins’ seminal 1969 work “Illicit Traffic of Pre-Colombian Antiquities” — for every discovery of a masterpiece like the Aphrodite, there are hundreds if not thousands of tombs destroyed.

Similar contortions abound in Eakin’s review. He calls our portrait of the Getty “cynical,” but goes on to say that no institution is more suited “to Verres-like scrutiny” than the Getty. He calls Chasing Aphrodite “an important book, but not in the way they intend.” Ultimately, we’re left to speculate about the “quite different interpretation” Eakin thinks can be drawn from the facts we lay out. His only hint comes in his final paragraphs, when he calls American museums’ decision to return more than half a billion dollars worth of looted antiquities “a victory…for the approach endorsed by collecting museums.” That is akin to calling the Battle of Gettysburg a clear victory for the South. The repatriations were a reluctant surrender to overwhelming facts, long denied, that exposed museums’ participation in a market awash in illicit antiquities.

Eakin is critical of the Italians for “waging their battle through the press” but largely omits that he was a frequent beneficiary of such leaks in his own coverage of the scandal for the New York Times and others. (For those requiring recent evidence, see Eakin’s recent scoop in the Times about Italy’s investigation of Princeton antiquities curator Michael Padgett.*)

Indeed, it was thanks to those scandalous Italian leakers that Eakin was the first American reporter to reveal the scope of the Italian investigation in 2002. But his report missed the key fact – the planned indictment of Getty antiquities curator Marion True. He explains this omission in his review by saying these leaky Italians “could not disclose” their plans for the curator because they “had not yet been made public.” What honorable behavior from the same Italians who Eakin says routinely manipulated the press.

Some of Eakin’s claims are almost laughable. He says, citing no evidence, that we encourage “readers to infer skullduggery in routine museum dealings.” Apparently Eakin finds the bribery, forgery, tax fraud, smuggling and general dishonesty that we document at the Getty – with what Eakin calls a “vast body of internal memoranda, legal briefs, and museum correspondence” — to be routine for the museum world. In truth, unlike Eakin’s review, our research and documentation leaves very little for our readers to infer.

As Eakin notes, our reporting stands out from the other coverage (including his own) in going far beyond what the Italian investigation uncovered. The bulk of our book is based on internal Getty documents, not the Italian investigation. Eakin claims, without any factual support, that these documents were “leaked from the office of the Getty’s in-house counsel.” While many of the files we cite were privileged, Eakin is wrong to presume that documents generated by the general counsel’s office must have been leaked from there. These confidential records span four decades and were circulated widely among senior staff, the board and outside counsel. Many were accessible to those far lower on the Getty totem pole. To suggest, as some have, that our reporting is based on leaks from a single “Deep Throat” is silly. As our more than 300 footnotes make clear, there were enough “Deep Throats” at the Getty to round out a Greek chorus.

Eakin particularly ties himself in logical knots when it comes to the book’s central character, former Getty antiquities curator Marion True.

Eakin calls our focus on True “puzzling” — an odd assertion for someone who wrote a 10,000 word profile of her for The New Yorker in 2007. If anything, it is Eakin who thrusts True to center stage, repeatedly comparing her “unprecedented” trial to Cicero’s historic prosecution of Gaius Verres, with True cast as the corrupt Roman governor. He laments True’s unjust treatment, but elsewhere says that like Verres, she faced “a huge body of evidence.” It is only thanks to our reporting that True can be seen in her proper context – that of a curator who proposed questionable acquisitions that were exhaustively debated and approved by a series of superiors above her on the chain of command.

After scolding us for focusing on True, Eakin scolds us for not providing more detail on her criminal trials. Her Italian trial concluded without a verdict in October 2010, after our manuscript was finalized. It was included only thanks to a last minute addition to the epilogue. As with her Greek trials, by the time of its ambiguous conclusion, the Italian case’s significance was largely moot.

As for factual issues, the most Eakin can muster from our 360-page book is a footnote that calls our account of True’s two undisclosed loans “puzzling.”

We reported that she accepted a loan of $400,000 from one of the Getty’s leading antiquities dealers – a clear ethical violation that, after it was confirmed by the Getty’s outside counsel, led to her dismissal. True refused to answer our questions about the transaction, and the dealer in question is dead. His nephew told us — on the record — that the loan was run through an off shore shell company created by a family attorney specifically to obscure the origin of the money – the dealer. Eakin finds the account unpersuasive, noting that True was charged 18% interest by the attorney. He ignores the fact that True was also charged interest by her close friends, collectors Lawrence and Barbara Fleischman, when she borrowed from them to repay the first loan. Eakin is the only reporter to have interviewed Marion True since her dismissal, yet offers no plausible explanation for why an offshore shell company would be needed for an above board transaction; nor why True failed to disclose the loan to her superiors, as clearly required by Getty policy; nor why the Getty demanded her resignation after (belatedly) investigating the transaction. As elsewhere, we’re left to wonder about Eakin’s lack of skepticism on this matter.

As for the second loan True received from the Fleischmans, Eakin is convinced it is being repaid, citing assurances True’s attorney made to Getty counsel in 2006. We’re left to wonder: Did Eakin inquire whether the Getty’s attorneys were satisfied by that assurance? Have True’s payments to her wealthy friends continued since 2006? In an interview this week, Stang acknowledged that during the period he reviewed, “there were some months when she missed the payments.” He said he does not know if True continues to make payments on the loan, which is unsecured by collateral.

These are among the many questions the remain unanswered about Marion True and her time at the Getty. In the years since she was indicted by Italy, we have requested to interview her dozens of times, to no avail. As we’ve noted, the only journalist granted that privilege was Eakin, under unclear conditions. The result was a lengthy and sympathetic account of True’s debacle that curiously failed to answer many of the most central questions that surround her. How could True present herself as a reformer while continuing to pursue the acquisition of looted antiquities? Was the Getty in good faith when it approved the acquisition of the Aphrodite on the very day True and other museum officials learned of an international investigation into its origins (not days later, as Eakin mistakenly wrote in the profile.) Why did True continue to pursue the acquisition of a golden funerary wreath just weeks after concluding it was “too dangerous”? And how could True profess ignorance about the illicit antiquities trade to Italian authorities after concluding as early as 1987 that “the majority of antiquities on the market were likely to have been removed from their countries of origin illegally.”

In the end, True remains – like the statue of an unknown goddess that ruined her – an enigma. The same could be said for Eakin’s review.

* An earlier version of this post incorrectly referred to Italy’s “indictment of former Princeton antiquities curator Michael Padgett.” Padgett, who remains a curator at Princeton, has been notified he is the target of an investigation but has not been indicted.