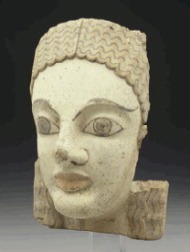

A remarkable document filed with New York’s Supreme Court on Friday reconstructs the journey of an ancient sculpture of a bull’s head from its theft during the Lebanese civil war through the shadowy corners and winding pathways of the international antiquities black market.

A remarkable document filed with New York’s Supreme Court on Friday reconstructs the journey of an ancient sculpture of a bull’s head from its theft during the Lebanese civil war through the shadowy corners and winding pathways of the international antiquities black market.

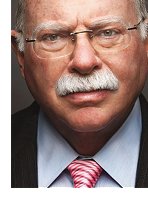

The filing, an application for a turnover order filed by Deputy DA Mathew Bogdanos, recounts a Grand Jury investigation that traced the stolen relic through a who’s who of the antiquities trade before ending up on loan at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where it was seized in July.

The filing, an application for a turnover order filed by Deputy DA Mathew Bogdanos, recounts a Grand Jury investigation that traced the stolen relic through a who’s who of the antiquities trade before ending up on loan at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where it was seized in July.

The 66-page filing is worth reading in full, as it bristles with insights into the antiquities trade that Bogdanos, the author of Thieves of Bagdad, has collected over more than a decade investigating antiquities trafficking networks. It is also a testament to the type of dogged investigation required to uncover the true history of a stolen antiquity.

Bogdanos’ investigation included the use of Grand Jury subpoenas, search warrants, interviews with witnesses in several countries and thousands of pages of shipping documents, customs forms and email correspondence.

“Nonetheless, even this investigation…has been unable to illuminate those well-appointed shadows where money changes hands and legitimate, but all-too-inconvenient, questions of the provenance and ownership history of the objects are frequently considered outre and ever so gauche,” Bogdanos writes. “Indeed, because so many shadows remain, and because the farther back we go the darker and more impenetrable are those shadows, it is best to trace the possession of the Bull’s Head backward…”

Anyone familiar with investigations of Mediterranean smuggling networks over the past two decades will recognize the dozen names associated with the object’s past.

The following summary of that shadowy journey does not do justice to the tale, but highlights the key players:

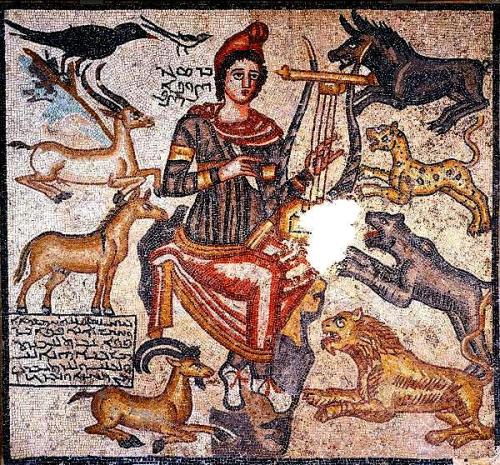

July 8, 1967: The bull’s head was excavated from the Temple of Eshmun in Sidon, Lebanon, by French archaeologist Maurice Dunand as part of a state-sponsored excavation.

1979: Amidst the raging Lebanese civil war, the bull’s head and other artifacts from Eshmun were transferred to Beirut and then to a storage area of the Byblos Citadel for safekeeping.

1981: Armed members of the Phalangist paramilitary group seized objects from the Citadel, including the bull’s head. After negotiations with the antiquities directorate, the Phalangists return many of the objects to the Citadel. But the bull’s head and dozens of other objects are not among them and disappear into the black market.

1980s: The Bull’s Head is associated with the George Lotfi Collection of Beirut and Paris and with Frieda Tchacos in Zurich (Nefer Gallery), according to a subsequent claim by the Met’s curator of ancient art Joan Mertens. Her source for this information is never clarified or documented.

April 11, 1991: Four sculptures stolen from Eshmun appear in an auction by the Numismatic & Ancient Art Gallery in Zurich. They are seized and returned to Lebanon.

December, 1994: Sotheby’s offers a male torso and a sarcophagus fragment from Eshmun for sale. Both are eventually seized and returned to Lebanon. Several more Eshmun objects are recovered over the years.

May 18, 1996: The Bull’s Head re-appears in shipping documents and was delivered to London antiquities dealer Robin Symes’ New York penthouse at the Four Seasons’ Hotel on 57th Street.

As Bogdanos notes, “There is not a single piece of paper known to exist on or about the Bull’s Head (C-17) between its disappearance from the basement storage room of the Byblos/Jubayl Citadel on August 14, 1981, and its brief appearance in the Transcon invoices in the summer of 1996…A neon sign flashing “stolen” would have been more subtle and less insidious.”

November 27, 1996: Symes sells the Bull’s Head for $1.2 million to Lynda and William Beierwaltes of Colorado, who display it in their dining room. While Symes assures them the object is authentic, as Bogdanos notes, “there was not a whisper-not even the faintest hint of a whisper about whether it was a lawful antiquity. Indeed, the lawfulness of the Bull’s Head (C-17) does not appear to have been part of any documented conversation between the Beierwaltes and Symes.” The Bull’s Head appears on the market “like Athena full-grown from the brow of Zeus,” Bogdanos writes, one of several flourishes in his filing.

November 27, 1996: Symes sells the Bull’s Head for $1.2 million to Lynda and William Beierwaltes of Colorado, who display it in their dining room. While Symes assures them the object is authentic, as Bogdanos notes, “there was not a whisper-not even the faintest hint of a whisper about whether it was a lawful antiquity. Indeed, the lawfulness of the Bull’s Head (C-17) does not appear to have been part of any documented conversation between the Beierwaltes and Symes.” The Bull’s Head appears on the market “like Athena full-grown from the brow of Zeus,” Bogdanos writes, one of several flourishes in his filing.

1998: The Bull’s Head and other objects in the Beierwaltes collection are displayed in an article in House and Garden. Christos Tsirogiannis, a forensic archaeologist specializing in identifying illicit antiquities, identified many looted antiquities in the Beierwaltes collection by matching the photographs in the article to photographs of looted antiquities contained in dealer archives.

2004: The Beierwaltes ask Max Bernheimer, Head of Christi.e’s Ancient Art & Antiquities Department, to appraise their antiquities collection. He appraised 115 objects in the collection at $51.5 million but never offered it at auction. Symes was revealed as their main supplier, the source of 97 of the 99 objects that listed a prior owner. “Symes was not just their main supplier, he was to all intents and purposes their only supplier: the direct, the essential, and clearly much-used link in a supply chain that started with the tombaroli and ended with the Beierwaltes,” Bogdanos writes.

2005: The Beierwaltes approach Hicham Aboutaam at Phoenix Ancient Art about selling the Bull’s Head and other antiquities in their collection, which is estimated to be worth $95 million. Phoenix appraises the value of the Bull’s Head at $1.5 million.

2005: The Beierwaltes approach Hicham Aboutaam at Phoenix Ancient Art about selling the Bull’s Head and other antiquities in their collection, which is estimated to be worth $95 million. Phoenix appraises the value of the Bull’s Head at $1.5 million.

2006: Phoenix ships the Bull’s Head and other objects from the Beierwaltes to Geneva, where it is kept in the Geneva Freeport. “According to Hicham Aboutaam, and as is standard procedure with shipments to the Freeports, and hence part of the sine qua non of their existence, the Bull’s Head went directly from the Geneva airport in a Swiss-customs-padlocked truck to the Geneva Freeport. And it left the Freeport the same way.”

2008: Phoenix requested a search for the Bull’s Head in the Art Loss Register database of stolen art. The ALR had been provided details about the stolen Bull’s Head in 2000 but mysteriously failed to enter it into their database of stolen art. ALR issued a certificate for the object — a fact that, in Bogdanos’ words, “highlight(s) the dangers of relying on an ALR search and nothing more for provenance research.”

2008: Phoenix Ancient Arts publishes images of the Bull’s Head in their Geneva catalog in advance of showing the Bull’s Head at the 24th Biennale des Antiquaires at the Grand Palais in Paris. After the Paris show, it is shipped back to Geneva.

September 2009: The Bull’s Head is shipped to New York, where hedge fund billionaire Michael Steinhardt expressed an interest after seeing it in the Phoenix catalog but claimed in an email he was too “broke” to buy it at the time.

August 10, 201O: Steinhardt acquired the Bull’s Head for $700,000 and left it on display at Phoenix Ancient Art’s New York Gallery.

October 2010: The Bull’s Head is loaned to by Met by Steinhardt through Phoenix Ancient Art Gallery. The only reference to its provenance is a single line of six words: “Ex-American private collection, collected in 1980’s-1990’s.” When the Met presses for more detail, Phoenix says The Beierwaltes aquired it from Symes.

2014: The Beierwaltes declare bankruptcy, declaring that their “primary business for much of their adult lives has been the acquisition, management and sale of an extremely extensive and valuable body of art works…[in]…a category of art known as antiquities.”

April 2014: Carlos Picon, the Curator in Charge of the Met’s Greek and Roman Department, noticed that the Bull’s Head on loan from Steinhardt appeared to be the same bull’s head missing from the Eshmun excavations. The object was removed from display and Aboutaam was notified.

April 16, 2014: Given the revelation, the Beierwaltes re-acquired the Bull’s Head from Steinhardt for $560,000 ($700k minus Aboutaam’s 20% commission). Steinhardt receives a piece of equal value from Aboutaam.

October 2016: Met General Counsel Sharon Cott writes to Steinhardt saying the Met intended to notify Lebanese authorities about the stolen Bull’s Head. William Pearlstein, the Beierwaltes’ attorney, acknowledged that the bull’s head was likely the one found in Eshmun but asked the Met not to contact authorities.

Dec. 5 2016: Met director Thomas Campbell notifies Lebanon that the bull’s head on loan to the museum appears to come from Sidon.

January 10, 2017: Sarkis Khoury, the Lebanese Director General of Antiquities, requests the return of the stolen Bull’s Head. He also writes to the Beierwaltes with a similar demand in March.

June 2017: Amid the District Attorney’s investigation, counsel for the Beierwaltes filed a pre-emptive lawsuit against the Lebanese Republic and the Manhattan DA’s office seeking to prevent the seizure of the bull’s head.

July 7, 2017: Acting on the request from Lebanese authorities, the DA’s office seized the Bull’s Head from the Met.

The full court filing can be found here and below:

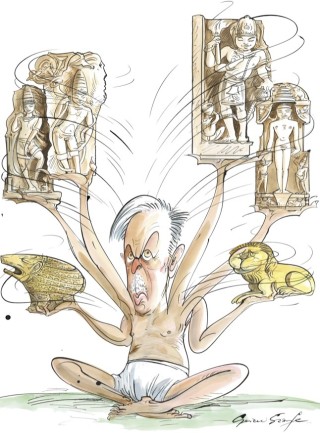

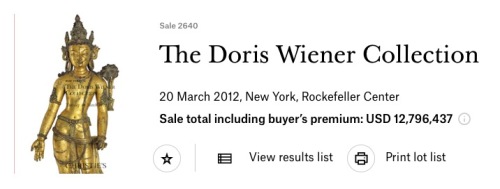

Antiquities dealer Nancy Wiener was arrested Wednesday morning in Manhattan and charged with conspiring with international smuggling networks to buy, smuggle, launder and sell millions of dollars worth of stolen Asian art thru leading auction houses.

Antiquities dealer Nancy Wiener was arrested Wednesday morning in Manhattan and charged with conspiring with international smuggling networks to buy, smuggle, launder and sell millions of dollars worth of stolen Asian art thru leading auction houses.

She sold the first to Singapore’s ACM without being asked to provide its ownership history, the complaint states. After I repeatedly asked the museum to release its records (to no avail), the museum appears to have contacted Wiener for additional information.

She sold the first to Singapore’s ACM without being asked to provide its ownership history, the complaint states. After I repeatedly asked the museum to release its records (to no avail), the museum appears to have contacted Wiener for additional information.

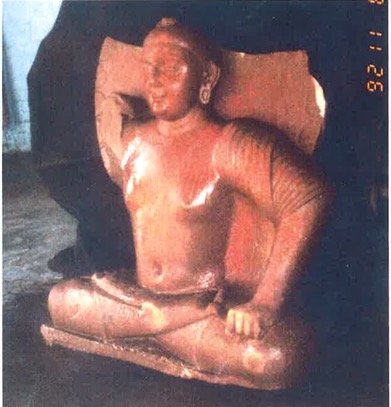

When Wiener consigned a Cambodian sculpture of 11th century Shiva at a 2011 auction at Sotheby’s, the auction house noted that cracks in the sculpture “had been dressed up with plaint splatters to mask repairs” – a clear sign of looting, according to the complaint.

When Wiener consigned a Cambodian sculpture of 11th century Shiva at a 2011 auction at Sotheby’s, the auction house noted that cracks in the sculpture “had been dressed up with plaint splatters to mask repairs” – a clear sign of looting, according to the complaint.

Lynch has had prior run-ins with the illicit antiquities trade in India. Court records filed this week quote a confidential informant telling authorities that Lynch “traveled to India roughly twice a year in the 1980’s while working for London Sotheby’s as the head of their Indian and Islamic Department in order to meet with Vaman Ghiya (an arrested antiquities dealer in India) to select recently looted artifacts for Sotheby’s auction.” Ghiya is a notorious convicted Indian antiquities smuggler who has been described as “the Indian

Lynch has had prior run-ins with the illicit antiquities trade in India. Court records filed this week quote a confidential informant telling authorities that Lynch “traveled to India roughly twice a year in the 1980’s while working for London Sotheby’s as the head of their Indian and Islamic Department in order to meet with Vaman Ghiya (an arrested antiquities dealer in India) to select recently looted artifacts for Sotheby’s auction.” Ghiya is a notorious convicted Indian antiquities smuggler who has been described as “the Indian

The first to match the Shantoo image to the Lahiri stele was Vijay Kumar, an Indian art enthusiast and

The first to match the Shantoo image to the Lahiri stele was Vijay Kumar, an Indian art enthusiast and

Wiener is a second generation antiquities dealer who runs one of the country’s most prestigious Asian art galleries on Manhattan’s East 74th Street. Last year we

Wiener is a second generation antiquities dealer who runs one of the country’s most prestigious Asian art galleries on Manhattan’s East 74th Street. Last year we  In the years since the Kapoor seizures, Easter and Bogdanos have been investigating the collectors and museums who bought from Kapoor and the suppliers who smuggled looted antiquities for him. Easter’s work on the case is highlighted in this short

In the years since the Kapoor seizures, Easter and Bogdanos have been investigating the collectors and museums who bought from Kapoor and the suppliers who smuggled looted antiquities for him. Easter’s work on the case is highlighted in this short