Last month the Boston Museum of Fine Arts voluntarily returned to Nigeria eight works of art — ranging from a terra-cotta Nok head dating to 500 B.C. to a wooden Kalabari memorial screen from the late 19th century — that the museum concluded had been stolen or looted.

The returns were not the result of a claim made by Nigeria but proactive research by the museum’s staff and curator of provenance Victoria Reed, who spent 18 months researching more than 300 objects bequeathed to the museum by William Teel, a wealthy benefactor and MFA overseer until his death in 2012.

The returns were not the result of a claim made by Nigeria but proactive research by the museum’s staff and curator of provenance Victoria Reed, who spent 18 months researching more than 300 objects bequeathed to the museum by William Teel, a wealthy benefactor and MFA overseer until his death in 2012.

As part of the review, Reed also checked the provenance of 108 objects previously donated by the Teels and the rest of the museum’s African and Oceania collection. Most objects had clear title, Reed said. About five objects remain under review, including a terra-cotta sculpture of a Pregnant Ewe from Mali that has been described as a looted fragment combined with a modern addition.

As part of the review, Reed also checked the provenance of 108 objects previously donated by the Teels and the rest of the museum’s African and Oceania collection. Most objects had clear title, Reed said. About five objects remain under review, including a terra-cotta sculpture of a Pregnant Ewe from Mali that has been described as a looted fragment combined with a modern addition.

The MFA should be commended for the proactive research that led to the returns. For decades, the Boston museum bought looted antiquities and dismissed questions about those objects from foreign countries, academics and investigative reporters – showing little regard for the public trust that comes with tax-exempt status. While there is more work to be done on the MFA’s collection, the museum’s recent behavior makes clear it has turned the page on that ugly history.

To address the mistakes of the past, more museums should follow the lead of the MFA and the Dallas Museum of Art by doing what they have done with Nazi-era paintings: proactive, transparent research into the provenance their antiquities collections.

THE AFRICAN TRADE

The Nigerian returns shed light on a branch of the illicit antiquities trade that receives relatively little attention: African art, which in the United States grew in popularity in the 1980s and – after many countries in the region had passed laws to protect their cultural heritage.

The MFA’s research concluded that all eight objects had been looted, stolen or removed from Nigeria without government permission, at times using what appeared to be falsified documents.

One of the objects was an Oron ancestral figure, or ekpu, that survived the Biafran war and was in the Oron museum as of 1970. In 2001, Teel’s records show the figure was acquired by Galerie Walu in Zurich, Switzerland, now owned by Jean David. It was accompanied by a document stating that the National Commission of Museums and Monuments had waived Nigeria’s ownership right to the object. The MFA contacted the commission and found that was not the case, suggesting the document was falsified. In an email, David said the object was sold by his father from his private collection, not through the gallery. David said he continues to research questions about the authenticity of the documents and has offered to get back to me with additional information.

One of the objects was an Oron ancestral figure, or ekpu, that survived the Biafran war and was in the Oron museum as of 1970. In 2001, Teel’s records show the figure was acquired by Galerie Walu in Zurich, Switzerland, now owned by Jean David. It was accompanied by a document stating that the National Commission of Museums and Monuments had waived Nigeria’s ownership right to the object. The MFA contacted the commission and found that was not the case, suggesting the document was falsified. In an email, David said the object was sold by his father from his private collection, not through the gallery. David said he continues to research questions about the authenticity of the documents and has offered to get back to me with additional information.

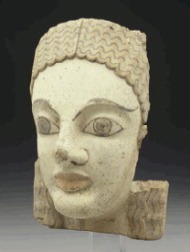

A 13th century Yoruba portrait head sold to the Teels by Montreal gallery Lovart International was said to have been in a private collection by 1980. But the MFA’s research suggests that a document allegedly signed by the former Director General of Nigeria’s National Commission for Museums and Monuments is not authentic. The gallery could not be reached for comment.

A 13th century Yoruba portrait head sold to the Teels by Montreal gallery Lovart International was said to have been in a private collection by 1980. But the MFA’s research suggests that a document allegedly signed by the former Director General of Nigeria’s National Commission for Museums and Monuments is not authentic. The gallery could not be reached for comment.

The Teel’s Nok terracotta head (right) dating perhaps as early as 500 B.C. was said to have been found near Kaduna State, Nigeria and taken to Europe, where it was acquired by the dealer Marc Leo Felix in Brussels. In March, 1994, Felix sold it to the Teels. Felix has not yet responded to my questions about the object.

The Teel’s Nok terracotta head (right) dating perhaps as early as 500 B.C. was said to have been found near Kaduna State, Nigeria and taken to Europe, where it was acquired by the dealer Marc Leo Felix in Brussels. In March, 1994, Felix sold it to the Teels. Felix has not yet responded to my questions about the object.

THE DAVIS GALLERY

The remaining five objects returned by the MFA came through the Davis Gallery in New Orleans. The gallery is owned by Charles Davis, a leading seller of African art since the 1970s.

A brass altar figure from the Benin people, seen at the top of his post, was apparently stolen from an ancestral altar in the Royal Palace of Benin City before the Davis Gallery acquired it in 1997. As the MFA states, “Although the figure was accompanied by documentation that appeared to authorize its sale by the chief of the guild of Benin City’s brasscasters, or Igun Eronmwon, inconsistencies within the bill of sale, as well as recent correspondence from the office of the Director General, National Commission for Museums and Monuments, Nigeria, have cast doubts upon the authenticity of this document.” An 18th century Edo head, below, was also acquired by the gallery in 1990 from the Benin brass casters.

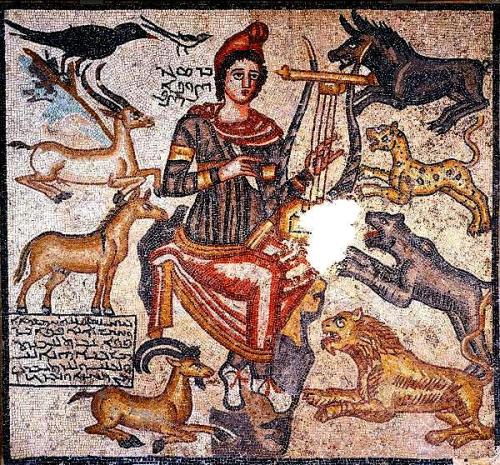

In 1994 the gallery sold a 2,000-year-old Nok sculpture (below) to the Teels on behalf of a dealer named Charles Jones. “Although documentation that appears to authorize the export of this object from Nigeria was issued in 1994, recent correspondence from the office of the Director General, National Commission for Museums and Monuments, Nigeria, has cast doubts upon this document’s authenticity,” the museum found.

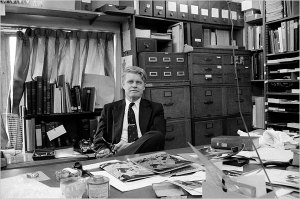

I recently spoke with Charles Davis about the MFA’s returns and his role in the market for African art over the years.

In the early 1970s, Davis was the director of a Virginia zoo. He and his wife Kent discovered tribal art while traveling across Africa in a Land Rover taking photos. “We traded with the pygmies, with tribes in Zaire,” he recalled. “We didn’t have money so we traded our clothes.”

Over the years, Davis “cultivated friendships with tribal people, traders, and African dealers and began to bring out fabulous objects,” recalled William Fagaly, the New Orleans Museum of Art curator of African Art, in an interview with Antiques magazine. “At that point, everybody stood up and took notice and in short order he became a dealer’s dealer, supplying work to the big boys who dominated the trade.”

The business of African art was slow until the 1980s, when the opening of the Michael C. Rockefeller Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art put it on the map, Davis said. “When the Met anointed it as fine art in 1981 by opening the Rockefeller Wing, the U.S. recognized it as fine art. Other than that it was worthless.” (Needless to say, parts of the Rockefeller Collection were gathered under questionable circumstances.)

Davis estimates he has sold some 10,000 African objects over the years, acquired during more than 150 buying trips to Africa. He says he’s been out of the African art business since 2005, when Katrina devastated his adopted home of New Orleans, where he operates the Davis Gallery out of his 1845 Greek Revival mansion (above) on the banks of the Mississippi. The business of African art has now largely moved to Paris and Brussels, he says.

Asked about the MFA’s returns, Davis is philosophical.

“I’ll take the hit,” he said. “I knew it was coming. I knew we were getting politically correct that nothing should be exported, and the people be damned.”

“I think the MFA has made a mistake,” he said. “To see American institutions to return a lot of the material in this political atmosphere….is going to be disastrous for these objects.” He notes unrest in the region:the terrorist group Boko Haram is active in the area; and during the Biafran war of the late 1960s, he said, a large part of the museum in Oron was looted.

“This is African language,” he said. “Africa never had a real written language. Their art was their way of communicating. There are great notions like abstraction that we’ve learned from. To deny this to the rest of world would be a travesty. Without these wonderful objects, without the story being told, there would be no Pablo Picasso. To put prohibition on these things is a step way over the line.”

Besides, he said, the trade in African art has greatly benefitted Africans. “The word stolen and looted is incorrect. I’ve seen Sotheby’s catalogs in remote villages. These things are sold as free expressions of their culture. They culminate in very high prices for these objects. They’re very aware of what these things are worth. Dealers like me have pumped millions of millions into Africa so they can buy the medicine they need. It’s a big enterprise and I’m proud that Africans have done extremely well. This is a renewable resource for Africa. People in Africa are very happy with the ability to sell things and realize a great benefit.”

How does Davis explain the falsified documents that apparently came with his objects? “A lot of these items have been sold by government officials. I’ve worked with very high officials who claimed to have the right to do so. I have provided those letters to people when I sold the objects.”

One of the pieces, a set of Kalabari screen figures (seen above), dates from the late 19th century, he said. “There were three wooden figures owned by men’s association. They were totally not used and discarded. Someone from that region realized these people wanted to sell them and they did…they worked their way through the pipeline to me. You can return all the archaeologics you want. But to have something as recent as 20 years ago decaying, to have that returned doesn’t make sense.”

Who was this middleman? “I don’t want to name the middleman…he was a government official, a member of Parliament….I’m going to protect my sources because philosophically I think they’ve done the world a great service. We’re trying to make sure these objects will survive millennia.”

A Campaign of Repatriation

Despite his opposition to the MFA’s returns, Davis says he firmly believes many archaeological objects now in Western collections should eventually be returned to Africa. In the 1980s, he said he proposed a massive campaign of repatriation of antiquities to Mali.

“I wrote a book called Animal Motif. I worked hand in glove with the Musée national du Mali. They told me the French were going to help them build a museum, so I went to see Susan Vogel,” a leading Africanist in the United States.

Davis says he proposed setting up a non-profit foundation so that American collectors could return their objects while receiving a tax benefit. “If clients could donate back to the country of origin and get a tax write-off they would go for it. I think it would be a good program. They can go back to encourage collectors to donate back to the country of origin, rather than having art seized and repatriated.”

But Vogel and other American museum curators discouraged him. “She thought it would not be workable,” he recalled. “Let’s watch and wait,” she told him. Others said: “Repatriation to Africa is not advised…The only thing that matters is the conservation of this art.”

“We’ve been watching and waiting ever since,” Davis said. “Maybe nows the time to do it.”

Would he support such an effort?

“I’m behind it 100%. It would be nice if there’s a tax incentive to do it. I think here could be a worldwide program to encourage us to do that…I would be first to do it.”