The Contested Temple Guardian

What does a 10th century Khmer temple warrior have in common with a Greek cult goddess from the 5th Century B.C.?

Quite a bit, it turns out. Both were objects of veneration whose remarkable craftsmanship represented the apex of their respective cultures’ artistic achievement. Both massive limestone statues were looted and purposely broken to make them easier to smuggle — telltale scars that decades later would bear witness to a violent and illicit origin. And both reveal a strikingly similar story about the ugly inner workings of the trade in ancient art.

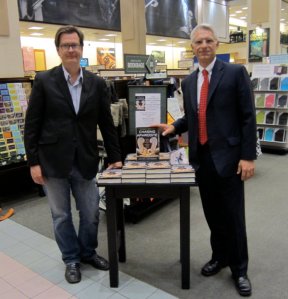

We told the story of the Getty’s goddess in Chasing Aphrodite. The story of the Khmer temple guardian is being told today in legal filings by Sotheby’s and the US Attorney’s office, which is suing for the return of the statue on behalf of Cambodia in a federal court in Manhattan. (We’ve written previously about the case here here and here.) Both parties agree the statue was removed at some point from an ancient temple complex at Koh Ker, where the statue’s feet remain to this day. The key question — unanswered in the government’s earlier filings — is when.

This month the U.S. Attorney’s office amended its original complaint with damaging new details that apparently came to light through pre-trial discovery of Sotheby’s internal correspondence. The filing, which we’ve embedded below, is worth reading in full. Among other things, it reveals how little the art world has changed since the 1980s, when the Getty bought its cult goddess amid clear signs the statute had been recently looted and then sought to cover up those illicit origins.

Here are some highlights:

Date of looting: The federal government is now stating that the Sotheby’s statue, representing Duryodhana, and its companion at the Norton Simon Museum, representing Bhima, were looted from a temple complex in Koh Ker “in or around 1972.” This addresses Sotheby’s earlier contention that the statue might have been removed sometime prior to the 1920s.

Intentional Damage by Looters: Like the Getty’s Aphrodite, the Koh Ker statues were intentionally dismembered to make them easier to smuggle:

“In the case of monumental statues like the [Sotheby’s warrior] the heads would sometimes be forcibly removed and transported first, with the torso following later, due to the difficulty of physically transporting the large torsos.”

In September 2010, this detail was noted by an expert hired by Sotheby’s to prepare a condition report on the statue.

“[The Scientist’s] theory is that the sculpture was either forcibly broken for ease of transport from the find site and then put back together later, or that the head and the torso did not belong together.”

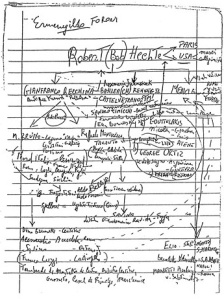

The feet of the two ancient sandstone statues were left behind by looters at a temple in Koh Ker, Cambodia.

The Scientist proposed a testing plan to determine which was the case. Instead of accepting that plan, Sotheby’s fired the expert, the complaint alleges. Readers of Chasing Aphrodite will recall that similar questions were raised about the head of the Aphrodite and the fresh breaks on the statue’s body (p. 93 – 94.) Luis Monreal, the head of the Getty Conservation Institute, proposed tests on soil and pollen found in the folds of the statue Aphrodite to determine its origin. The Getty Museum instead opted for ignorance.

Market Path: The amended complaint specifies that after they were stolen from Koh Ker by “an organized looting network,” the statues at Sotheby’s and the Norton Simon were smuggled to Bangkok and delivered to a Thai dealer, who sold them to a “well known collector.” The New York Times has identified that dealer as Douglas A. J. Latchford. (Latchford co-authored a book on Khmer art with Emma Bunker, the expert cited in previous filings as saying in emails to Sotheby’s that the statue had been ‘definitely stolen.’) Latchford allegedly conspired with the London auction house Spink to obtain false export permits for the statues and they were transported it to London in 1971 or 1972, the amended complaint states. The Duryodhana was sold to a Belgian businessman in 1975, and his widow consigned it for sale by Sotheby’s in 2010.

Market Path: The amended complaint specifies that after they were stolen from Koh Ker by “an organized looting network,” the statues at Sotheby’s and the Norton Simon were smuggled to Bangkok and delivered to a Thai dealer, who sold them to a “well known collector.” The New York Times has identified that dealer as Douglas A. J. Latchford. (Latchford co-authored a book on Khmer art with Emma Bunker, the expert cited in previous filings as saying in emails to Sotheby’s that the statue had been ‘definitely stolen.’) Latchford allegedly conspired with the London auction house Spink to obtain false export permits for the statues and they were transported it to London in 1971 or 1972, the amended complaint states. The Duryodhana was sold to a Belgian businessman in 1975, and his widow consigned it for sale by Sotheby’s in 2010.

Sotheby’s Deceit: The complaint alleges Sotheby’s knowingly misled potential buyers, Cambodian officials and U.S. investigators about the statue’s ownership history, claiming it had been seen in the UK in the late 1960s — well before the 1970 UNESCO convention. In fact, the government alleges, Sotheby’s knew the statue had been with Latchford in SE Asia until the early 1970s. To support their claim, the complaint cites emails between Sotheby’s and Latchford, who is described as “the original seller of the sculpture back in 1975.” One of those internal emails reveals Sotheby’s concerns about how the statue’s provenance will affect its sale:

“The most important question is the provenance. Can [the Collector] tell us if he acquired this sculpture before 1970? That’s the standard [an art advisor to a prospective buyer] is applying. It’s what his client wants.”

“Sotheby’s inaccurate representations dating the [statue’s] appearance in the United Kingdom to the late 1960’s, rather than after 1972, therefore eliminated a significant obstacle to the selling the [statue,]” the complaint states.

Indeed, Latchford’s name was omitted from the object’s stated ownership history.

In a statement to the New York Times, Sotheby’s denied the government’s claims, saying the U.S. attorney’s office was trying “to tar Sotheby’s with a hodgepodge of other allegations designed to create the misimpression that Sotheby’s acted deceptively in selling the statue…That is simply not true.”