Robert Hecht called the other day to say he’d received the copy of Chasing Aphrodite that we sent to his home on Boulevard La Tour Maubourg in Paris.

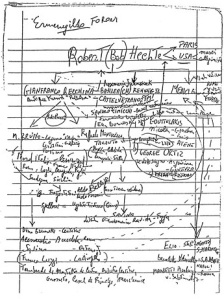

This chart showing the key players in the illicit antiquities trade was seized by Italian police in the 1990s.

Hecht is the American antiquities dealer who has dominated the trade for more than 50 years. Italian authorities believe he was also a mastermind of the international blackmarket in looted art — his name appeared at the top of an organization chart of looters, middlemen and dealers that Italian police found in the early 1990s. When Getty antiquities curator Marion True was indicted in 2005, Hecht was named as her co-defendant. His criminal trial in Rome on charges of trafficking in looted art continues today.

Here’s how we describe “the preeminent middleman of the classical antiquities trade” on page 30:

“Since the 1950s, Hecht had sold some of the finest pieces of classical art to emerge on the market. […] His network of loyal suppliers reached deep into the tombs and ruins of Greece, Turkey, and Italy. […] His clients included dozens of American and European museums, universities, and private collectors, including J. Paul Getty, whom Hecht had once persuaded to buy an intricately carved Roman bust. For decades, Hecht single-handedly dominated the antiquities market with his brilliance, brutality, and panache. He cited Virgil as readily as the lyrics of Gilbert and Sullivan, and he was known to break into operatic arias. He often drank to excess and was known to gamble his money away in all-night backgammon games. He tamed competitors with an unpredictable temper and eliminated rivals with anonymous calls to the police. Even those who sold directly to museums gave Hecht a cut of the deal, earning him the nickname ‘Mr. Percentage.'”

Robert Hecht poses in front of the famous looted Greek vase he sold the museum in 1972 for $1 million.

That’s the first of nearly thirty references to Hecht in Chasing Aphrodite. Even so, we felt it was short shrift for a man whose role in the art market is truly legendary. During our interviews and meetings with Hecht over the years, he was always a pleasure to deal with. He is an engaging dinner companion, often charming and talkative while being coy about the key details we were scratching for. Today, at 92 years old, he suffers from some health problems but retains the sharp wit he’s long been known for.

So, what did Hecht think of the book? “It was a well written book except for one lie, which I hope was not your invention,” he said.

Hecht was not disturbed by the allegations that he virtually ran the illicit antiquities trade for 50 years. He wasn’t upset about being called a gambler and an abusive alcoholic, or a participant in a massive tax fraud scheme, or the man largely responsible for the destruction of thousands of archaeological sites. The offending passage was the reference to Hecht “eliminating rivals with an anonymous call to the police.” We based it on conversations with Italian law enforcement sources. Hecht assures us it is not true.

“The accusation of being a squealer is very serious,” Hecht said. “That is not in my blood.” Hecht said such accusations could be bad for business, which has been slow lately: “A customer might say, oh my god, you’re a spy for the police.” Hecht’s wife Elizabeth got on the phone next to explain that the charge had troubled her husband: “A lot of people we know did do that, but Bob never did. He’s not a rat, and does not wish to be known as such.”

Many in the trade recall how Hecht threatened to expose his rivals in a memoir he was writing. He never followed through on those threats — the unpublished memoir was seized by Italian authorities and is now among the most compelling evidence against him at trial.

But dropping a dime to the police is different. Going back over our notes, there is only one specific case Italian authorities cited in suspecting Hecht of being “a squealer.” It involved the Getty’s 1988 acquisition of the statue of Aphrodite from Hecht’s rival, London dealer Robin Symes.

Shortly after the whopping $18 million acquisition — a record at the time –Interpol Paris received an anonymous tip claiming the Aphrodite had been looted from Morgantina, Sicily. The tipster named the looters and middlemen in the transaction with detail that later proved remarkably accurate. Italian authorities have long suspected the source was Hecht, who lived in Paris at the time and may have been jealous of his rival Symes. But the Italians have no proof of their hunch, and Hecht flatly denies being the tipster.

Given his clear denial, and absent further supporting evidence from our Italian sources, we agreed to correct the record. Robert Hecht is many things, but to the best of our knowledge, he is not a squealer.

We’ve invited Hecht to join us later this month in his hometown of Baltimore, where we’ll be speaking at the Walters Museum on October 29th. He will be in the States that week and did not rule out the possibility of joining us.

Was J. Paul Getty a Nazi collaborator?

Was J. Paul Getty a Nazi collaborator?