In Sunday’s LA Times, Jason has an article on his recent trip to Aidone, Sicily, where the return of the Getty’s goddess has revived a debate about her true identity: Aphrodite, or Persephone?

The vista of central Sicily from the ruins of Morgantina, where the statue of Aphrodite was illegally excavated in the late 1970s.

“In ancient times, central Sicily was the bread basket of the Western world. Fields of rolling wheat and wildflowers, groves of olive and pomegranate and citrus — even today, fertility seems to spring from the volcanic soils surrounding Mt. Etna as if by divine inspiration.

It was here on the shores of Lake Pergusa that ancient sources say Persephone, the goddess of fertility, was abducted by Hades and taken to the underworld. She was forced to return there for three months every year, the Greek explanation for the barren months of winter.

Ancient sources say it was while picking flowers along the banks of this lake, a short drive from Morgantina, that Persephone was abducted by Hades and taken to the underworld.

When Greek colonists settled the region some 2,500 years ago, they built cult sanctuaries to Persephone and her mother, Demeter. The ruins of Morgantina, the major Greek settlement built here, brim with terra-cotta and stone icons of the two deities.

It seems a fitting new home for the J. Paul Getty Museum’s famous cult statue of a goddess, which many experts now believe represents Persephone, not Aphrodite, as she has long been known.

The Getty goddess in her new home in the archaeological museum in Aidone, Sicily.

Since the Getty’s controversial purchase of the statue in 1988 for $18 million, painstaking investigations by police, curators, academics, journalists, attorneys and private investigators have pieced together the statue’s journey from an illicit excavation in Morgantina in the late 1970s to the Getty Museum.

The Getty returned the goddess to Italy this spring, and a new exhibition showing the statue and other repatriated antiquities from a private American collector and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York was inaugurated here last week.

The archaeological museum in Aidone, Sicily

The goddess’ new home is a 17th century Capuchin monastery that now serves as the archaeological museum in Aidone, a hilltop village of about 6,000 residents. The cozy museum, which holds up to 150 visitors at a time, contains the most important objects discovered in the nearby ruins of Morgantina.

During its 22 years at the Getty Museum, the statue was virtually ignored by scholars, thanks largely to the aura of controversy that surrounded it. But as the scandal recedes, new, deeper mysteries about her are finally coming to the fore.

Who is the goddess? Does her slightly awkward marble head really belong atop the massive limestone body? Where precisely was she found? And what can she tell us about the ancient Greek colonists who worshipped her some 2,400 years ago?

The fact that so little is known about the marble and limestone statue — one of the few surviving sculptures from the apex of Western art — illustrates the lasting harm brought by looting and the trade in illicit antiquities. As the goddess was smuggled through the black market, she was stripped of her meaning and rendered a mute object of beauty.

The one thing scholars agree upon is her importance. The goddess’ clinging, windblown drapery is a clear reference to Phidias, the Greek master who a few decades earlier carved the figures that adorned the Parthenon in Greece — many of which now reside in the British Museum.

“It’s one of the very few examples we have from the high Classical period,” said Katerina Greco, a Sicilian archaeological official and leading expert in Greek art who wrote one of the few studies of the statue. “There is nothing like it in Italy.”

Today, central Sicily is an underdeveloped backwater of Europe. Just 17,000 visitors currently see the archaeological museum in Aidone where the statue now sits. At the Getty, about 400,000 saw her every year.

Residents here hope that the statue’s return marks the beginning of a new chapter, one focused on economic development and a deeper understanding of the goddess’ identity and significance.

“The statue didn’t exist by herself, she was made for a specific place and a particular purpose,” said Flavia Zisa, president of Mediterranean archaeology at the University of Kore in nearby Enna.

Most experts today agree the goddess most likely does not represent Aphrodite, as former Getty antiquities curator Marion True surmised when she proposed the statue for acquisition. But because some key fragments are missing from the goddess, scholars remain divided.

Greco has argued that the goddess represents Demeter, noting her matronly build and the remains of a veil covering her hair, a feature most often identified with older women in Greek times. In a forthcoming study, New York University professor Clemente Marconi will expand on his argument that the goddess is Persephone.

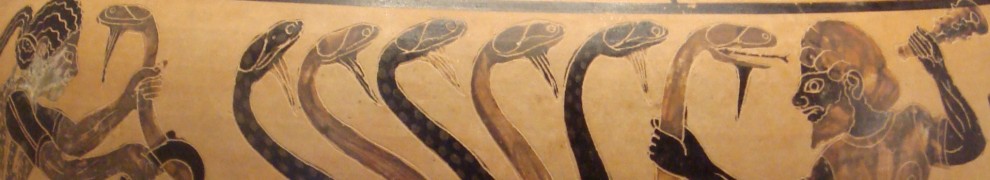

A terracotta Persephone on display in the same gallery as the goddess. Many experts now believe the Getty goddess is not Aphrodite.

In an acknowledgement of the changing views of the statue’s identity, Sicilian officials have re-branded the statue as the “goddess” of Morgantina and abandoned earlier references to Venus, the Roman name for Aphrodite.

More definitive answers to the mysteries of the goddess may rest with the looters who dug her up. If the statue’s exact excavation spot were known, archaeologists could re-excavate the area and build a better understanding of her purpose.

But omerta — the Sicilian oath of silence — has long kept that key piece of information a secret. Whispers in Aidone tell of two shepherd brothers who found the statue on the eastern flank of Morgantina where a sanctuary to Demeter and Persephone has been found.

“It is time for them to speak,” said Silvio Raffiotta, a local prosecutor who investigated the statue’s looting in the 1990s. “Now there is no risk.”

![]() “Felch and Frammolino are serious men, investigative reporters at the top of their games, who very intelligently lay out all the issues at stake here, and you’d probably do best to read this one sitting up straight.

“Felch and Frammolino are serious men, investigative reporters at the top of their games, who very intelligently lay out all the issues at stake here, and you’d probably do best to read this one sitting up straight.