Former Getty Antiquities Curator Marion True

One of the most scathing rebukes of the collecting practices of American museums in recent memory came not from a grumpy archaeologist, a nosy journalist or an overzealous foreign prosecutor. It came from one of the museum field’s rising stars: Getty antiquities curator Marion True.

In June 2000, True delivered a gutsy speech to an audience of museum peers that denounced them for relying on “distorted, patronizing and self-serving” arguments to justify their collecting of ancient art. Over the course of the next hour, True dismantled the various justifications museums had long used to buy ancient art that was almost certainly looted.

The speech, whose full text we’ve posted and annotated here, is remarkable not just for True’s scathing remarks but also for their venue: the annual gathering of the Association of Art Museum Directors. The group is the museum profession’s most powerful, consisting of representatives from the country’s largest and wealthiest collecting institutions. As such, the AAMD wields immense clout on matters of institutional policy, including collection practices.

Philippe de Montebello, former director of the Met

Under the sway of former directors Philippe de Montebello of the Met and James Cuno of the Art Institute of Chicago (now CEO of the Getty), the AAMD had long resisted the 1970 UNESCO Convention, which calls for import restrictions and international cooperation to stop trafficking in illicit antiquities. Instead, AAMD’s guidelines were riddled with caveats and loopholes that allowed member institutions to buy undocumented antiquities as long as the pieces were artistically “significant.” In her speech, True was calling out the power structure of American museums.

James Cuno, CEO of the J. Paul Getty Trust

Her speech was inspired by an earlier panel at Columbia University on the Elgin Marbles. The discussion “had nearly devolved into a fistfight” when a fellow panelist suggested the Parthenon sculptures needed to remain the British Museum because the Greeks were “unworthy custodians and therefore did not deserve to have it” [sic]. “As the three front rows of the audience were primarily of Greek nationals or Greek Americans, this statements did not go down very well,” True noted dryly.

True said the debate had caused her to re-trace the evolution of what had become an increasingly nasty debate about cultural patrimony that pit foreign officials and archaeologists against American museums, dealers and collectors. “Given the seemingly noble intentions that inspired the foundation and development of American Art museums, how have they now come to be so often in direct conflict with the source countries and the academic communities that work on cultural heritage?”

Her answer laid the blame squarely at the feet of American museums, which had used similarly “demeaning arguments” to justify their acquisition of marquee objects and to brush off the concerns of foreign countries. She listed the most common arguments, many of which are still used today:

“–Because the contemporary population was ethnically not the same people as the creators even thought they inhabit the same territory;

–Because the police force in the source country does not do enough to protect its patrimony and maybe even is in collusion with the smugglers;

–Because art historians in the country are not up to the job of studying their own patrimony but have had to look to the British German and American scholars for leadership;

–Or because the national laws governing the protection of cultural properties are repressive since they do not allow the free trade in the objects that US laws allow and,

–Or most perplexingly and inflammatory, in the case of Italy, because Mussolini had continued to enforce the laws instituted in the 18th century to protect Italian artistic heritage, that we would be enforcing the laws of a fascist regime.”

“Surely,” True said, “we should not have to rely on such distorted, patronizing and self-serving observations to justify collecting ancient art in this country.”

Next, she turned her sights on dealers and collectors, who still “vehemently denied” the extent of looting that has been clearly documented by archaeologists and governments. Their claims that the illicit trade was small were “contradicted by the evidence,” including their own political machinations to gut American laws prohibiting the import of such objects. It was time to accept that most undocumented antiquities came not from “old European collections,” as dealers and museums were fond of claiming, but from recent chance finds or illegal excavations, True said.

Likewise, the claim made by Sothebys and other auction houses that sellers preferred not to reveal provenance information “flew in the face of logic” because such information would only increase an object’s value. And the common practice of asking governments for evidence of whether a piece had been looted “conveniently ignores” the fact that, by definition, such objects are “undocumented,” she said.

She concluded with a knock-out punch: “Most museums have long preferred to consider objects innocent until proven guilty,” she said, citing the Getty’s own 1987 acquisition policy and the writings of James Cuno while at the Harvard Arts Museums. “But experience has taught me that in reality, if serious efforts to establish a clear pedigree for the object’s recent past prove futile, it is most likely—if not certain—that it is the product of the illicit trade and we must accept responsibility for this fact.

“It has been our unwillingness to do so that is most directly responsible for the conflicts between museums, archaeologists and the source countries.”

In one fell swoop, True had laid bare the cynical path of many museum masterpieces—a path few insiders had ever been willing to publicly acknowledge.

But as powerful and succinct as True’s presentation was, her listeners could have been forgiven a measure of skepticism. While it represented one side of Marion True – the crusader for reform — they knew another: the accomplished curator and competitor who for a decade had used those very same tactics to fill the Getty with some of the best undocumented pieces in the world. Indeed, True’s intimate knowledge of museums’ efforts to navigate the illicit trade was based on her personal experience.

As it happened, the day after True gave her speech a judge in Switzerland ruled that Italian officials could take possession of hundreds of Polaroids and documents that had been seized in a 1995 raid of an antiquities dealer’s Geneva warehouse. The Polaroids showed scores of looted artifacts as they appeared fresh from the ground. Eventually Italian investigators traced the greatest number to the Getty and Italian prosecutors started planning a prosecution of Marion True.

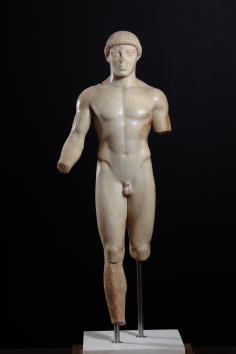

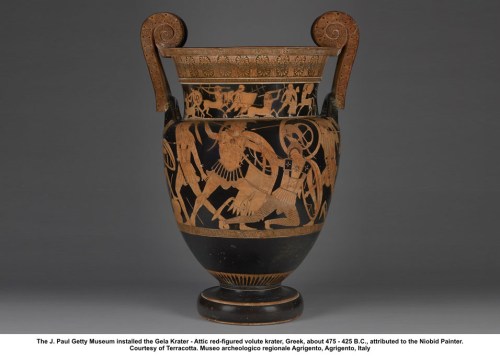

A Polaroid of the Getty's Statue of Apollo showing it soon after being looted

Soon after, an internal Getty probe found similar photos in True’s own curatorial files showing, in the words of the Getty’s outside counsel, “objects in a state of disrepair or in a location from which they may have been excavated.” The Getty’s attorney concluded it would take little for the Italians to link True to a conspiracy or to support a claim that the curator “knew or should have known that many objects acquired by the Getty were illegally excavated from Italy.”

Among their best evidence, he noted, would be True’s own 2000 speech before her peers at the AAMD.

![]() October 26th: The National Arts Club in New York City hosts Jason for 6:30pm lecture and book signing. 15 Gramercy Park South. (Members and guests only.)

October 26th: The National Arts Club in New York City hosts Jason for 6:30pm lecture and book signing. 15 Gramercy Park South. (Members and guests only.) October 26th: Archaeological Institute of America The Institute’s New York Society will host Ralph for an evening talk about Chasing Aphrodite. Details here.

October 26th: Archaeological Institute of America The Institute’s New York Society will host Ralph for an evening talk about Chasing Aphrodite. Details here. October 27: Harvard Club of NYC will be hosting us for a lecture, book signing and dinner. (Members only.)

October 27: Harvard Club of NYC will be hosting us for a lecture, book signing and dinner. (Members only.)![]()

October 29: Walters Museum of Art in Baltimore. Museum Director Gary Vikan will be moderating a public talk with Ralph, Jason and Arthur Houghton, the former interim Getty antiquities curator and a staunch advocate of collector’s rights. Discussion at 2pm, followed by book signing. Details here.

October 29: Walters Museum of Art in Baltimore. Museum Director Gary Vikan will be moderating a public talk with Ralph, Jason and Arthur Houghton, the former interim Getty antiquities curator and a staunch advocate of collector’s rights. Discussion at 2pm, followed by book signing. Details here.

October 19th: Princeton University.

October 19th: Princeton University.

That evening at 6pm, Penn Law and the Museum will host us for a discussion on the illicit trade with Robert Wittman, former head of the FBI’s

That evening at 6pm, Penn Law and the Museum will host us for a discussion on the illicit trade with Robert Wittman, former head of the FBI’s  October 24th: New York University.

October 24th: New York University.  November 2: Chapman University. The Department of Art and Chapman Law School will host Jason for an evening lecture and book signing. Details TBA.

November 2: Chapman University. The Department of Art and Chapman Law School will host Jason for an evening lecture and book signing. Details TBA.

The festivities included a jam session by David and his old band; grilled oysters from the nearby Puget Sound; and a delicious Frogmore Stew (aka Low Country Boil) prepared by Liz and Ben Fischer, our friends from North Carolina.

The festivities included a jam session by David and his old band; grilled oysters from the nearby Puget Sound; and a delicious Frogmore Stew (aka Low Country Boil) prepared by Liz and Ben Fischer, our friends from North Carolina.

Was J. Paul Getty a Nazi collaborator?

Was J. Paul Getty a Nazi collaborator?