UPDATE: Law professor Derek Fincham has commented on Italy’s case: “Using a domestic court to seek the seizure of an illegally exported object from another country has not been attempted before. But Italy has been at the forefront of repatriation strategies. This novel approach could lead to a new legal tool for nations of origin to pursue, if it can convince the Attorney General and a U.S. District Court to enforce this seizure order. The Getty appealed the earlier ruling, and they did so for a reason, this case could set a precedent which would open up museums to seizure suits in the nation of origin.” We’d be interested to hear more legal analysis of this issue.

UPDATE: David Gill notes a comment by the Italian prosecutor saying that the ruling leaves the Getty “little room for maneuver.”

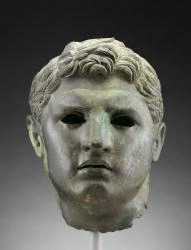

The Getty had a significant setback in the legal case over one of its most important antiquities — the bronze statue of a victorious athlete known as the Getty Bronze.

Here’s Jason’s story in the LA Times. We’ve posted the judge’s complete ruling below.

An Italian court has upheld an order for the seizure of a masterpiece of the J. Paul Getty Museum’s antiquities collection, finding that the bronze statue of a victorious athlete was illegally exported from Italy before the museum purchased it for $4 million in 1976.

The ruling Thursday by a regional magistrate in Pesaro will likely prolong the legal battle over the statue, a signature piece of the Getty’s embattled antiquities collection whose return Italian authorities have sought for years.

“This was the news we were waiting for,” said Gian Mario Spacca, president of the Marche region where the statue was hauled ashore in 1964, in an interview with Italian reporters. “Now we will resume contacts made with the Getty Museum to build a positive working relationship.”

Spacca visited the Getty last year hoping to negotiate an agreement to share the statue. But the Getty has made clear it will fight in court to keep the piece and is expected to appeal the ruling to Italy’s highest court.

“We’ve not yet seen the ruling and won’t comment until we do so,” said Getty spokesman Ron Hartwig.

The long battle over the bronze athlete — one of the few complete Greek bronzes to have survived and believed by some to have been made by Alexander the Great’s personal sculptor Lysippus — is a lingering reminder of the controversy that has surrounded the Getty’s collection of ancient art.

Since 2005, the Getty has voluntarily returned 49 antiquities in its collection, acknowledging they were the product of illegal excavations and had been smuggled out of their country of origin. Hundreds of other objects were returned by other American dealers, collectors and museums. In the wake of those returns, several American museums struck cooperative deals with Italy and Greece that allow for long-term loans of ancient art.

But such agreements have not shielded American museums from further claims that ancient art in their display cases are the product of a black market responsible for the destruction of archaeological sites around the world. In March, Turkish officials revealed they were seeking the return of dozens of allegedly looted antiquities from the Getty, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Cleveland Museum of Art and Harvard’s Dumbarton Oaks.

Most such repatriation claims have been settled without legal action. The dispute over the Getty’s bronze ended up in Italian court thanks to its complicated legal status — an accidental discovery in international waters off Italy’s Adriatic coast.

The statue was most likely lost at sea after being plundered by Roman soldiers in Greece around the time of Christ. (The government of Greece has never asked that the statue be returned there.)

In 1964, Italian fishermen found the statue snagged in their nets. They hauled it ashore in the small port town of Fano, buried it in a cabbage field and then hid it in a priest’s bathtub rather than declare it to customs officials, as required under Italian law.

Three brothers and the priest were convicted of trafficking in stolen goods, but an appeals court threw out their convictions in 1970, citing insufficient evidence. At the time, the statue was still missing, and its value was unknown.

In the early 1970s, the statue resurfaced in London, where millionaire oilman J. Paul Getty first became enamored of it.

Getty himself never authorized the purchase of the statue because he had concerns about its legal status, records show. In 1974, Italian officials tried to seize the statue in Germany, where it was being restored, but authorities there would not honor the request.

It was only after Getty’s death in 1976 that his namesake museum purchased the statue, ignoring the legal conditions its founder had placed on the acquisition, according to documents related to the case. The statue was one of the museum’s first acquisitions and was dubbed the “Getty Bronze.”

The bronze was one of dozens of ancient objects demanded by Italy during a lengthy fight with the Getty in recent years over its antiquities collection, much of which was acquired from middlemen who trafficked in objects looted from Italian tombs and ruins.

Talks broke down when the Getty refused to include the bronze on a list of objects it was willing to return. The impasse was broken only when a new criminal case about the bronze was filed in Italian court in 2007, taking it off the negotiating table.

That case has wound through the Italian legal system ever since. In February 2010, a judge ordered the statue’s return, citing the Getty’s “grave negligence” when acquiring a statue. The Getty appealed that ruling to Italy’s highest court, which sent the case back to the judge in Pesaro, not far from the port where the statue was first hauled ashore. The Getty has argued that the seizure order is invalid because no underlying crime has been proved.

If the high court ultimately upholds the seizure order, Italy will still have to convince U.S. authorities to enforce the order and seize the statue from the Getty Villa, where it is on display today in its own humidity-controlled room.

Read the full story of the Getty Bronze here.

Here’s the complete text of the May 3rd ruling:

Edward Perry Warren’s three-volume A Defence of Uranian Love, written under his pseudonym Arthur Lyon Raile and privately printed in 1928-1930…is the clearest elucidation of the motives that lay behind his acquisition of Graeco-Roman antiquities for the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and other prominent collections. Warren’s acquisition practices converted those antiquities into a “paederastic evangel,” as he himself declares, and his Defence is intimately woven into this lifelong, evangelistic mission.

Edward Perry Warren’s three-volume A Defence of Uranian Love, written under his pseudonym Arthur Lyon Raile and privately printed in 1928-1930…is the clearest elucidation of the motives that lay behind his acquisition of Graeco-Roman antiquities for the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and other prominent collections. Warren’s acquisition practices converted those antiquities into a “paederastic evangel,” as he himself declares, and his Defence is intimately woven into this lifelong, evangelistic mission.