Malcolm Bell’s review of our book Chasing Aphrodite (WSJ, July 1) concurred with our central finding—that American museums fueled the destruction of knowledge by acquiring looted antiquities and using what Bell calls a “fabric of lies” to obscure their complicity in an illicit trade.

The review takes a befuddling turn, however, in Bell’s defense of Marion True, the former Getty antiquities curator at the center of the book.

Bell recommends True be hired for “a major museum position.” He is apparently unbothered by glaring conflicts of interest. As we detail in the book, True twice accepted secret six-figure loans from two of the museum’s most prominent sources of ancient art. It was those loans — not her indictment by Italy for allegedly trafficking in looted art — that ended True’s career, ruined her professional reputation and silenced many of her most ardent supporters. The ethics policy of Bell’s own university bars such conflicts, as would common sense. Yet Bell urges us to ignore them.

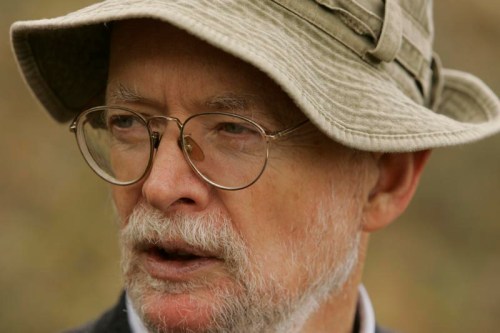

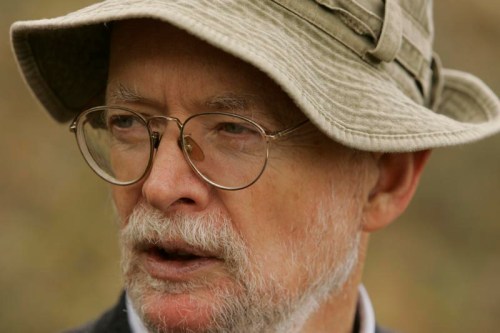

Archaeologist Malcolm Bell, who has led the American excavation at Morgantina since the early 1980s.

Elsewhere in the review, Bell says we “undervalue” True’s efforts at reform. In fact, we took pains to research True’s path as a reformer, and our book details many efforts that had not previously been published. For example, under the Freedom of Information Act we obtained a previously unreleased copy of her remarks before the Cultural Property Advisory Committee arguing in favor of import restrictions on Italian antiquities, a position that won her no favor with museum colleagues. Her defense of Italy’s request (which was drafted by Bell) proved influential in the panel’s subsequent decision to grant it.

Bell also claims we “repeatedly cast doubt on her actions and motives.” In his view, after some “unwise” acquisitions, True underwent a “radical change of course” in 1995, and her subsequent reforms did far more good than the harmful practices in her past. While it is tempting to think of the curator’s story as a Pauline tale of conversion, True’s actions are more complex than that, and more troubling. Over her two decades as curator, True often acted as the reformer and the acquisitive curator at the same time. She appears to have adopted both identities, and used them to accomplish her ends as the circumstances required. It is this conflicted behavior that raise questions about True’s motives.

For example, in 1988, just months after completing the acquisition of the clearly looted statue of Aphrodite, True denounced a Cleveland dealer for trying to sell a Cypriot mosaic of similarly dubious origins. In 1993, when True was offered a suspect ancient funerary wreath in a Swiss bank vault, she took the high road, declining the offer because it was “too dangerous.” Yet months later, she changed her mind and recommended the wreath’s purchase.

In 1995, True led the reform of the Getty’s acquisition policy, but a year later violated the spirit of her reform in order to acquire the antiquities collection of her close friends Lawrence and Barbara Fleischman. (It was her colleague and confidant John Papadopoulos who considered the move hypocritical, not us, as Bell claims.)

And in 2001, long after her supposed conversion, True proposed the acquisition of a bronze Poseidon, withholding troubling information about its origins in what Getty attorneys concluded was “materially misleading.”

Are True’s conflicting actions a sign of hypocrisy? Ernest indecision? Remarkable self-blindness? Only True knows for sure, and we leave the question to the reader to decide. (In polls on this site, six of ten readers said they would not hire her, and seven in ten think she was guilty of trafficking in looted antiquities.)

In the end, we share some of Bell’s obvious sympathy for True’s plight. Until recently, she was the only American curator targeted by Italy for a practice that has long been rampant in American museums. And we share his sense of injustice that none of True’s superiors or peers were held to similar account. As we wrote in the book’s epilogue, “True, at once the greatest sinner and the greatest champion of reform, has been made to pay for the crimes of American museums.”

But sympathy should not blind us to the troubling complexities of True’s actions. Bell would do well to heed his own advice when he writes that True’s “bitter experience offers lessons to all parties.” Sadly, in the end it was not True’s conflicted crusade for reform that brought about the dramatic changes we have seen in recent years. It was her downfall.

![]() We’re honored to announce our work has been recognized with a Beacon Award from Saving Antiquities for Everyone (SAFE), the non-profit organization dedicated to the preservation of cultural heritage worldwide.

We’re honored to announce our work has been recognized with a Beacon Award from Saving Antiquities for Everyone (SAFE), the non-profit organization dedicated to the preservation of cultural heritage worldwide.