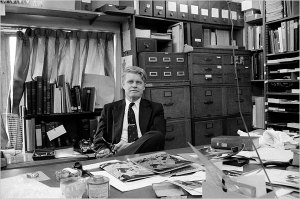

American antiquities dealer Robert Hecht died in February 2012 after six decades at the top of the trade in recently looted Classical antiquities.

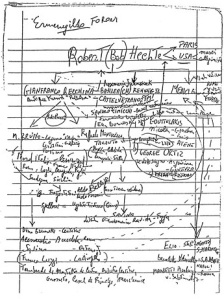

I’ve recently learned that some of that infamous career will be recounted when Hecht’s memoir is privately published in the coming months. The book is based on Hecht’s handwritten memoir, seized by Italian authorities from his Paris apartment and used as evidence against him at his Italian criminal trial. (I have a copy of Hecht’s notes and can assure you that he names names!) That account will be supplemented and expanded upon by a series of interviews Hecht conducted with Geraldine Norman, a former art market correspondent for the Independent.

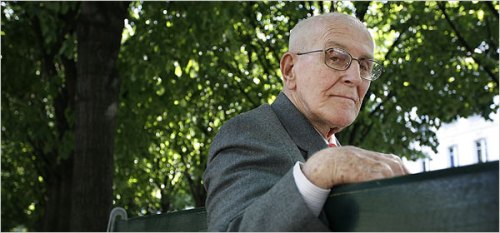

Hecht on trial in Rome, 2006

It’s not clear how widely available the book will be for sale, but Hecht’s account will almost certainly be incomplete. His trafficking network spread tens of thousands of looted ancient sculptures, coins and vases across museums and collectors around the world.

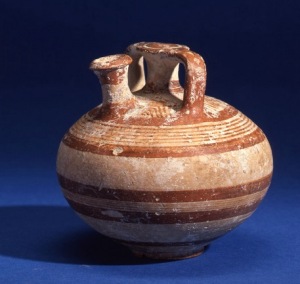

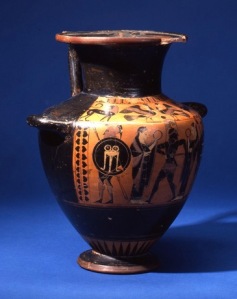

How should museums handle those Hecht objects in their collection today? That is the question I tackle in a forthcoming article in the alumni magazine for Haverford College, Hecht’s alma mater. Haverford’s current exhibition of Greek vases tied to Hecht serves as a good model for others museums wrestling with his sticky legacy.

The full article, which will appear in Haverford’s alumni magazine in late November, includes comments from alumni James Wright, Brian Rose, Edward L. Bleiberg, Carlos Picon (kinda), Jeremy Rutter and Patty Gerstenblith.

Here’s an excerpt:

Jenna McKinley has spent much of her life visiting museums. But it was only recently that she began thinking about how ancient objects had ended up in those museum vitrines.

The question arose while McKinley, a Haverford class of 2015 art history major and classics minor, was researching a collection of ancient Greek vases given to Haverford more than two decades ago by George and Ernest Allen, twin brothers who graduated from the college in 1940.

The Allen brothers acquired most of the ancient vases, McKinley learned, from Robert E. Hecht, Jr. ’41, a Latin major who went on to become one of the world’s leading—and most controversial—dealers in ancient art.

Over a storied six-decade career, Hecht sold tens of thousands of pieces of ancient art to leading museums and private collectors around the globe. Throughout, he was dogged by accusations that his wares had been recently—and illegally—excavated from tombs and ruins across the Mediterranean.

Over a storied six-decade career, Hecht sold tens of thousands of pieces of ancient art to leading museums and private collectors around the globe. Throughout, he was dogged by accusations that his wares had been recently—and illegally—excavated from tombs and ruins across the Mediterranean.

In the 1960s, Hecht was thrown out of Turkey and banned for life from Italy for allegedly trafficking in looted antiquities. In the 1970s, he sold the Metropolitan Museum of Art its famous “hot pot,” the Euphronios krater, whose $1 million price tag and mysterious origins immediately sparked claims that it had been looted. In the 1980s, Hecht was part of an alleged tax-fraud scheme involving the donation of hundreds of looted antiquities to the J. Paul Getty Museum near Los Angeles. And in 2005, he was criminally charged by Italy as the mastermind of an international looting and smuggling ring.

Hecht died in 2012, weeks after that Italian criminal case ended with no verdict, because the allotted time had expired. Despite a lifetime of allegations, he was never convicted of a crime.

As McKinley discovered in her research during the summer of 2013, the Allen collection, which became part of Magill Library’s Special Collections, was an artifact of Hecht’s long, colorful career. From the 1950s until the 1970s, George Allen worked as Hecht’s Philadelphia sales representative, publishing a biannual catalog of antiquities under the name Hesperia Art. Over the years, he arranged for his brother Ernest to purchase several vases from Hecht.

As McKinley discovered in her research during the summer of 2013, the Allen collection, which became part of Magill Library’s Special Collections, was an artifact of Hecht’s long, colorful career. From the 1950s until the 1970s, George Allen worked as Hecht’s Philadelphia sales representative, publishing a biannual catalog of antiquities under the name Hesperia Art. Over the years, he arranged for his brother Ernest to purchase several vases from Hecht.

McKinley excavated this hidden history over the next year, poring through yellowing college records and dusty Hesperia catalogs and reading books about Hecht’s role in the illicit antiquities trade. Her findings, along with the 20 Greek vases that inspired them, went on display in October in the Sharpless Gallery in Magill Library. The exhibit, titled Putting the Pieces Together: Antiquities From the Allen Collection, runs through Jan. 2.

It is rare for the history of an antiquities collection to be discussed so openly. Museums, while dedicated to education, often reveal little about where and how they obtained their ancient art, something McKinley hopes her exhibition can help change.

“We display the objects themselves regardless of their cracks,” McKinley writes in the essay that accompanies the exhibit, “but too often we try to ignore the fragmented nature of their more recent histories.”

Terry Snyder, the librarian of the college, conceived of the project in the fall of 2012 during conversations with Associate Professor of Classics Bret Mulligan. Both recognized that revealing the history of the vases could invite a claim for their return by Italy, where they were likely found. But the opportunity for a valuable educational experience outweighed the risk, Snyder and Mulligan concluded.

“If you collect things and hide them away, the world loses,” says Snyder, who tapped McKinley to research and curate the exhibit. “These questions about the vases and other antiquities are big ones that really create an opportunity for learning. Each item has its own biography. What can these materials teach us? This exhibit is a great opportunity for our students to delve into these issues, to raise questions about cultural patrimony, and to see where they lead. Haverford students are not afraid of hard questions. That goes back to the College’s Quaker values and our educational values.”

The Allen exhibit puts Haverford squarely in the middle of an international conversation about the role that museums and universities have played in the illicit antiquities trade, a global black market supplied by looters and smugglers and stoked by the art market’s demand for ancient relics.

As McKinley learned, the story of how ancient objects came to sit on the shelves has, until recently, been largely hidden. Over the past decade, however, those stories have begun to come to light, thanks to criminal investigations, probing journalists, and growing demands from foreign countries that their cultural relics be returned.

The ensuing controversy has shaken this corner of the art world to its roots.