UPDATE 8/9/14: The Sunday Times has published another devastating report on the Art Loss Register’s business practices. ALR Founder Julian Radcliffe admits paying thieves to recover stolen art in a dozen cases and is described as a “fence” by senior European law enforcement officials.

UPDATE: A 9/20/13 story in The New York Times reveals other questionable dealings of ALR and the departure of General Counsel Chris Marinello.

UPDATE 9/13: We’re told there have been several recent departures of senior staff from the Art Loss Register. They include Alice-Farren Bradley, a recovery specialist; MaryKate Cleary, who researched Nazi looting claims until she left for MOMA; and Ariane Moser, who managed European clients. That leaves Radcliffe, general counsel Chris Marinello, antiquities specialist William Webber and a handful of others.

Thirty years ago, a Getty antiquities curator coined the phrase “optical due diligence” — creating the appearance of caution while continuing to buying suspect antiquities.

Today, that continues to be the favored approach for much of the art world. Museums, auction houses, private collectors and dealers all claim to vet ancient art to make certain it was not illegally excavated. Yet we keep learning that the vetting process failed to prevent the acquisition of recently looted art.

A key facilitator of this fiction is the Art Loss Register, a for-profit registry based in London. ALR charges nearly $100 for a search of its files, touted as “the world’s largest database of stolen art.” In return, a client receives a certificate stating “at the date that the search was made the item had not been registered as stolen.” Sadly, that caveat-laden certificate has become the coin of the realm for due diligence in the art world.

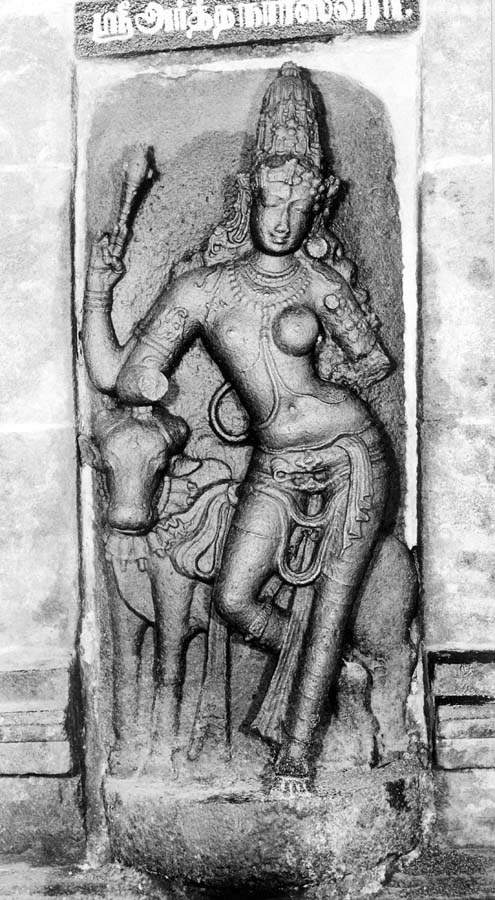

As we revealed recently, the certificate offered no protection to the National Gallery of Australia, which purchased a stolen bronze Shiva after receiving an ALR search certificate from antiquities dealer Subhash Kapoor:

The NGA was merely the latest to learn that, when it comes to antiquities at least, ALR certificates are not worth the paper they’re printed on. David Gill recently noted that the ALR claims to protect buyers, but appears to have provided certificates for the Christies sale of antiquities that have since been tied to known loot dealers Giacamo Medici, Robin Symes and Gianfranco Becchina.

Tom Flynn recently wrote that the ALR “is not a force for good,” adding that “a virtual market monopoly in Due Diligence provision is not good for the art market.” He cited this example of ALR’s shady dealings outside the area of antiquities:

In 2008, it was revealed that the company had been approached by a Kent art dealer, Michael Marks, who was seeking to conduct Due Diligence on a painting by the Indian Modernist artist Francis Newton Souza, which Mr Marks was hoping to buy. Marks was told by ALR chairman Julian Radcliffe that the painting was not on the ALR’s database of stolen art. It was.

In the court judgment issued by Justice Tugenhadt, it emerged that: “After Mr Marks had paid the search fee, he spoke to Mr Radcliffe. It is common ground that Mr Radcliffe told Mr Marks that if Mr Marks were to buy the Paintings, he, Mr Radcliffe, had a client who was interested in buying them from Mr Marks. Mr Marks asked Mr Radcliffe whether there was a problem with good title, and Mr Radcliffe said that there was not. It is common ground, and Mr Radcliffe accepts, that he misled Mr Marks.”

Given this history, we were curious why the ALR continues to issue certificates for ancient art — and why the art world continues to accept them as evidence of anything. In June, Jason contacted ALR founder Julian Radcliffe for his views on the issue. Here are excerpts from our conversation:

Jason Felch: Why does ALR provide search certificates for ancient art when there is obviously no documented theft when most antiquities are looted?

Julian Radcliffe: We are aware of the fact that our certifications are waved in the air saying, ‘Look what a good boy we are.’ We don’t like that. Ten years ago, the police and Carabinieri came to us and said, ‘Your certifications are being abused by bad guys who are waving them around as proof of clear title.’ We all know illegal excavations are not in the database. So 10 years ago we said, we’ll stop giving any certifications for antiquities, a difficult area. Then, when we had a further meeting [with law enforcement], they said the certifications are quite useful to police, as they give an audit trail. And if dealers don’t ask you [for one], it’s of great interest because that’s evidence they’re trying to suppress the fact. So we continued to issue them, at the request of law enforcement.

JF: Who, specifically, asked you to continue providing certificates for antiquities?

JR: I won’t say. And the Carabinieri would deny it if asked, of course.

JF: In 2007, Subhash Kapoor provided no provenance for the Shiva when asking ALR to search its database. Does ALR require provenance today?

JR: We are now insisting they give us some provenance….Where appropriate we try to check the provenance they give us through the British Museum and have made important discoveries. We are not going to be able to detect everything, particularly forged provenance.

JF: When did you start requiring provenance? And what amount of provenance do you require to run a search?

JR: In the last few months. We had a meeting with an auction house this morning, saying that they must give us more provenance…We require the generic information on the current holder and the date that the holder got it. We need a starting point if the certification is challenged later. You told us this was held by a dealer in Paris. If challenged, we would then ask, What’s the name of the dealer? So we can then make the dealer, through a court order, reveal who the parties were. The trouble is very often some of these items genuinely don’t have a full provenance. There are a lot of items out in the market that might have been exported legally, but nobody knows.

JF: So your “provenance” policy doesn’t even require the name of a previous owner until a piece is challenged. Why not require provenance going back to the 1970 UNESCO accord?

JR: I’d love to do that but they [the dealers] would make it up. What I would like to do is to get the source countries and archaeological community to recognize the fact that the antiquities trade would not go away. It continues. One of the problems is that minimalist architectural design favors antiquities and there’s a great demand from interior decorators. The market isn’t going to collapse. So we’ve got to regulate and police it. Reintroduce partage to make the legitimate market and the illicit market very clear. At least we’ve got a clear policy.

JF: Is ALR profitable?

JR: We haven’t made a profit for 10 years. I’ve invested 1 million pounds. I’ve made enough money in other companies that I don’t’ have to worry about it not making additional money. It’s been very hard to get clients to pay. Over half of our income comes from searching people, under half from recovery fees for insurance. Some 40 percent of our income is from recovery. In antiquities we get no recovery fees. The victims can’t pay. It’s a really bad area for us. The rest is from search fees. Half of that comes from auction houses and the other from dealers, museums, collectors, etc. That corresponds to roughly to 50% of the art market.

JF: Who are your biggest clients?

JR: Our clients include all the major auction houses. A few auction houses won’t search, but Bonhams, Christies and Sotheby’s all use us. It’s no secret that a number of them would like more help from us in this antiquities market. The antiquity dealers have been more inclined to search than dealers in other items.

JF: The NGA’s Shiva is unusual for an antiquity because it had been documented before it was stolen. A year or so after Kapoor received an ALR certificate for the stolen Shiva, Indian authorities posted online images of it with details of the theft. Yet ALR did not make the connection. Why not? Does ALR search past certificates to see if new information has surfaced?

JR: We go around those sites and take items…We employ 25 people in India doing back office searching. A number have worked in the Indian cultural heritage department. But the big issue is with IT: We have a database of 300,00 – 400,000 stolen items to search against the 2.5 million searches we’ve done in the past. If we search against all those previous searches, it slows down the search too much. And we couldn’t digitize the old searches, not back to 1991.

JF: How many certificates did ALR provide to Subhash Kapoor over the years?

JR: We’re looking into it.

Later via email Radcliffe added, “We are passing on your request for the number of certificates to the law enforcement to whom we gave all the information and will revert when we hear from them.”

No word since.

UPDATE: David Gill, writing with Christos Tsirogiannis in the 2011 Journal of Art Crime, notes that the major auction houses have routinely relied on the Art Loss Register to defend the sale of objects linked to notorious antiquities traffickers including Giacomo Medici, whose archives showing thousands of recently looted antiquities is apparently not included in ALR’s database.

When The Hindu informed local authorities about the theft, the case was immediately referred to the

When The Hindu informed local authorities about the theft, the case was immediately referred to the

The Art Gallery of New South Wales has released provenance information for one of the six objects it purchased from Subhash Kapoor, the New York antiquities dealer currently facing trial in India for trafficking in looted art. (Past coverage

The Art Gallery of New South Wales has released provenance information for one of the six objects it purchased from Subhash Kapoor, the New York antiquities dealer currently facing trial in India for trafficking in looted art. (Past coverage

Digital images allegedly sent to Kapoor by smugglers, however, suggest it was in India in 2006.

Digital images allegedly sent to Kapoor by smugglers, however, suggest it was in India in 2006.

So far, the NGA has failed the transparency test. As a member of the International Council of Museums, the museum is bound by a

So far, the NGA has failed the transparency test. As a member of the International Council of Museums, the museum is bound by a

UPDATE: The New York Times

UPDATE: The New York Times