A civil lawsuit filed today by the U.S. government sheds startling new light on the brutality of the Syrian looting operations of the Islamic State.

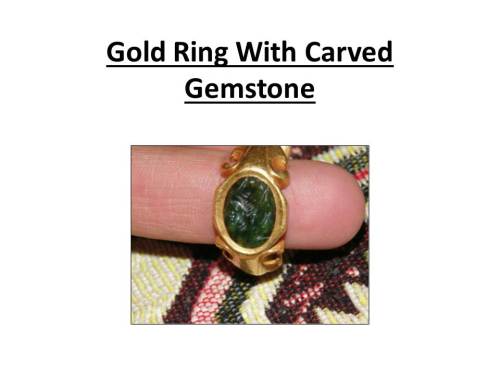

The lawsuit seeks the forfeiture of four looted objects – a gold ring, two gold coins and a stone relief – that were allegedly sold by the Islamic state to fund terrorism. Photographs of the objects were recovered during the May 2015 special forces raid on Abu Sayyaf, an ISIS leader in Deir Ezzor, Syria charged with managing the region’s Ministry of Natural Resources, which included looting operations.

The records show Sayyaf, who was killed in the raid, was part of a well-organized looting bureaucracy that ISIS used to generate revenue, as shown in this organization chart that was found among the documents recovered from his house:

As a regional chief, Abu Sayyaf issued looting permits and charged looters a Khums tax, 20% of the value their finds. He also had the ability to arrest individuals excavating archeological objects without authorization.

Much of the evidence from the Sayyaf raid cited in the case was first released publicly in November 2015 – and greeted with some skepticism by experts on the illicit trade, including myself. In particular, the raid fueled the heated debate about how much revenue ISIS actually generates from looting. The seized documents showed just $211,000 in revenue generated by the looting tax, suggesting the millions in looting revenue cited in some news accounts could be far off the mark.

Objects seized from Abu Sayyaf during a special forces raid in May 2015

But Thursday’s filing includes new records from the Abu Sayyaf raid that have not previously been released. Among other things, they include a harrowing account from looters who were extorted by ISIS – Abu Sayyaf ordered their child kidnapped when they refused to pay an low-ball price for a cache of gold and relics they had discovered.

The four objects being sought were shown in electronic images seized from Abu Sayyaf during the raid and were sold directly by him, according to the complaint. As detailed below, the FBI’s subsequent investigation was able to find additional information about at least one of the objects as it passed through the illicit trade.

Taken together, the newly released records give us a detailed but narrow window into ISIS’ efforts to profit off the international market in ancient art.

Like the evidence released before it, these new records should be considered critically – particularly at a time when a U.S. military intervention in Syria appears more likely. It is worth asking why the U.S. government has filed the complaint now, more than a year and a half after the evidence was gathered; why the government seeks the forfeiture of objects whose current location is unknown; and why this information is being released publicly, when it virtually guarantees the objects will not surface on the art market.

UPDATE 12/16/16: On Friday, I spoke with Arvind Lal and Zia Faruqui in the US Attorneys Office of the District of Colombia. Lal is the chief of the Asset Forfeiture and Money Laundering Section and Faruqui is the Assistant U.S. Attorney from that section who did much of the work on the complaint. Here is a summary of their answers to the questions above.

Where are the objects? Lal and Zia declined to say whether they knew where the objects were, citing the on-going investigation of the Abu Sayyaf material. But they said the complaint makes clear they are not currently in the United States.

Why file the complaint now? Lal said that the time between the May 2015 raid and the forfeiture complaint was necessary to conduct a thorough investigation of the records seized from Abu Sayyaf, consult with experts on the objects depicted in those records, coordinate with other federal agencies (FBI, State, Treasury and “other government agencies”) and compile the complaint. “We feel like we’ve done our homework with respect to these four items,” Lal said, suggesting that additional items may be added to the complaint in the future.

What is the strategy in filing a complaint against missing assets? “By filing this action, we hope we’ve dropped the market value of these four items to zero, along with anything else that may have passed through the hands of ISIS. Hopefully the market is now on notice that if something goes through the hands of ISIS, that item is subject to being seized.”

The most revealing exchange, in my view, was Lal’s response to my question about the strategy. Filing the complaint makes it nearly certain that these will never surface, I pointed out. Why not monitor the art market to see where they pop up and seize them at that time?

“I have a case load from narcotics to fraud to national security cases,” Lal said. “I don’t have a staff available to monitor the international art market. When I find out about a crime, I feel obligated to do what I can.”

Where there political motives driving the decision to file? “I’m a prosecutor,” Lal said, “I don’t give an damn about the politics of this.”

The Looted Objects

The four objects described in the forfeiture complaint range in estimated value from $50,000 to a few thousand dollars, and date from various periods and civilizations found in Syria. Below I’ve posted below the highest resolution images available from the U.S. Attorney’s office, along with details described in the federal complaint.

- A gold ring, photographed in November 2014, may depict the Greek goddess of fortune, Tyche and dates to approximately 330 BC – 400 AD. It is believed to come from Deir Ezzor, Syria. Investigators found an earlier picture of the same ring showing soil embedded in the carving, suggesting it had been recently excavated and was later “enhanced” for international sale, the complaint alleges. The ring was part of a set that sold previously (presumably in Syria) for $260,000.

2. Another photograph recovered from Abu Sayyaf shows a Roman gold aureus dated to 138 – 161 A.D. showing Antoninus Pius on one side and the goddess Liberalitas on the reverse. It was photographed in November 2014 and may have been looted from one of the numerous Roman or Greek sites in Syria, the complaint states.

3. A second gold coin depicted on images found on Abu Sayyaf’s hard drive shows Emperor Hadrian Augustus Caesar saying from 125 – 128 AD, the complaint states.

3. A second gold coin depicted on images found on Abu Sayyaf’s hard drive shows Emperor Hadrian Augustus Caesar saying from 125 – 128 AD, the complaint states.

4. The fourth object, depicted in an image found on Abu Sayyaf’s WhatsApp account on his cellphone and created in August 2014, shows a stone relief with cuneiform writing. The inscription, which is legible from the photographs, is an Assyrian dedication to King Shalmaneser III (859 – 824 BC). The object is believed to be from the archaeological site of Tell Ajaja in northern Syria. The relief has an estimated value of $30,000 – $50,000, the complaint states.

4. The fourth object, depicted in an image found on Abu Sayyaf’s WhatsApp account on his cellphone and created in August 2014, shows a stone relief with cuneiform writing. The inscription, which is legible from the photographs, is an Assyrian dedication to King Shalmaneser III (859 – 824 BC). The object is believed to be from the archaeological site of Tell Ajaja in northern Syria. The relief has an estimated value of $30,000 – $50,000, the complaint states.

Looters Testify about Extortion, Kidnapping under ISIS Antiquities Authorities

ISIS’ taxation system for looted antiquities has an obvious flaw: the value of the finds are difficult to know before they are sold on the international market. As a result, the basis for the Khums tax imposed by Abu Sayyaf’s department was often quite arbitrary. Not surprisingly, this led to conflicts between looters and their ISIS tax collectors.

Remarkably, one of these disputes is detailed in the newly released documents. The records show that ISIS authorities concluded that Abu Sayyaf had used his position of power to extort looters and kidnap one of their children when they refused to pay ISIS levies.

Remarkably, the documents seized from Sayyaf include direct testimony from some of his victims, who filed a complaint with the Islamic State’s General Supervising Committee. A redacted translation of the testimony, as well as images of the original document, is included in the forfeiture complaint. What follows is an account based upon these records:

In 2013, seven women from the village of al-Duwayr spent eight months digging with pick axes in the al-Salihiyyah archaeological site outside Damascus. (There are two locations named al-Salihiyyah in Syria, but as Paul Barford notes in the comments below, given the context this likely refers to the site outside Deir ez-Zor, where Abu Sayyaf was based.) During the illicit dig they found a cache of gold and other ancient relics.

The women asked a male relative, whose name is redacted, to sell the finds, but he could not reach an agreed upon price with local merchants, who offered up to $180,000. (It is not clear what currency is being discussed, but else where the records note many deals were transacted in U.S. dollars.)

Abu Sayyaf’s deputy, Abu Layth, learned of the find and came to collect the ISIS Khums tax, 20% of the discovery’s value. He put the value of their discovery at just $70,000 and offered to buy it all. When the looters refused the low ball price, Abu Layth attempted to take one-fifth of the find in lieu of the tax. That too was refused by the women.

Days later, Layth and five members of the Islamic State arrived at the house of one of the looters in masks and toting guns. Abu Layth, brandishing a pistol, demanded to know where the gold was. The women said it had already been taken to Turkey.

At that point one of the ISIS men grabbed a 15-year-old boy. Abu Layth stated, “I will take the boy to al-Raqqah and I will not bring him back until you bring the gold.”

The boy testified about his abduction, saying he was blindfolded, beaten in the back of the vehicle, threatened with a pistol to his head and then held for 15-days in al-Raqqah.

In his own testimony, Abu Layth acknowledged he had no experience with antiquities. He had worked for the ministry of natural resources for nine months, and had previously sold clothes and food.

Abu Layth testified that he was given $130,000 to purchase the relics but offered only $70,000 to the looters. Merchants in Turkey, who he communicated with “via mediators,” said the finds could be worth as much as $200,000. He said he had arrested the boy at the order of his boss, Abu Sayyaf.

Having heard the testimony, the Islamic State’s General Supervising Committee issued its ruling: Abu Sayyaf should fire Abu Layth, hire own responsible men, and apologize to the family for arresting the boy without justification.

Below are links to the federal complaint and attachments containing the documents it references. I welcome your additional thoughts in the comments section.

Federal complaint: https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/3239356-Forfeiture-Complaint-Stamped-Copy-12-15-16.html

Attachments to the complaint: https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/3239355-Attachments-to-Forfeiture-Complaint.html