*UPDATED: See below for additional information from RISD and Harvard Art Museums.

Dr. Arnold-Peter Weiss, the Rhode Island coin collector arrested Jan. 3 for felony possession of an ancient coin that authorities say he knew was recently looted from Sicily, has deep ties to the Rhode Island School of Design. He is a former trustee of the university and currently serves as former* chairman of the board of the university’s museum, to which he has donated several objects.

According to the criminal complaint against Weiss, he told a confidential informant wearing a wire that he knew where the coin “was dug up two years ago.” Weiss is innocent until proven guilty, and his lawyer has not responded to two requests for comment. If the allegations hold up in court, its appears to be a fresh example of the alarming link between the black market in looted antiquities and (apparently) respectable collectors and museums that we detail in Chasing Aphrodite.

According to the criminal complaint against Weiss, he told a confidential informant wearing a wire that he knew where the coin “was dug up two years ago.” Weiss is innocent until proven guilty, and his lawyer has not responded to two requests for comment. If the allegations hold up in court, its appears to be a fresh example of the alarming link between the black market in looted antiquities and (apparently) respectable collectors and museums that we detail in Chasing Aphrodite.

By participating in the illicit antiquities trade, museums and collectors betray their professed educational mission and encourage the destruction of context that happens as objects are looted and laundered through the black market.

Weiss appears to understand the importance of context in ancient art. In September 2010, when RISD reinterpreted and reinstalled its gallery of ancient, medieval and early Renaissance art, Weiss and his wife, Dr. Yvonne Weiss, a pediatrician in Barrington, RI, were major sponsors of the renovation.

“As a collector of ancient coins,” Dr. Weiss said in a press release from RISD, “my hope for this gallery—and for the entire reinstallation of the Radeke Building—is to provide visitors of all ages with context for understanding these fascinating and beautiful objects.”

The museum describes its collection of Greek, Roman and Etruscan art as “one of the finest collections of any university museum in the country,” and contains about seven hundred ancient coins spanning more than 1500 years. Among the collection highlights on the museum’s website are several recent acquisitions. Collecting histories are not provided for most objects.

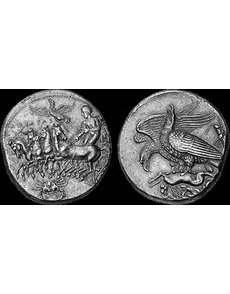

In 2010, Weiss donated a silver Greek tetradrachm, ca. 460 BCE from Naxos. The obverse is shown here. Details and the reverse, showing Silenos holding a kantharos, can be found on the museum’s website here.

A similar coin is listed here on the website of Nomos AG, the Swiss coin dealership that Weiss launched around 2007. The Nomos coin is said to be from the Randazzo (Sicily) Hoard of 1980 and is described as “one of the greatest and best known of all 5th century Greek coins.” It sold at auction recentlyfor 775,000 CHF, well over the 400,000 CHF estimate. Weiss’ partners at Nomos are Victor England and Eric McFadden of the Classical Numismatics Group and Alan Walker, who has a doctorate in Classical Archaeology from the University of Pennsylvania.

Note: The Syracuse Decadrachm previously listed here was not a donation by Dr. Weiss but an acquisition made by the museum in 1940, according to RISD director of marketing Donna Desrochers.

Another Weiss donation to RISD is a Flemish oil painting by artist Hendrik van Steenwyck, ca. 1550-1603. Details can be found here.

We’ve contacted the museum’s curator of ancient art, Gina Borromeo, to request additional details about these objects and any others Weiss may have donated.

We’ve sent a similar request to the Harvard Art Museums, where Weiss’ bio says he is was on the collecting committee until this month. The collection of the Arthur M. Sackler Museum, in particular, has an impressive collection of ancient coins.

We’ll post answers here when we get them.

*Harvard UPDATE: Jennifer Aubin, the Harvard Art Museums public relations manager, provided the following information: “Dr. Peter Weiss was a member of our Collections Committee, an advisory group, from 2006–2012. We have no objects in our collections donated by or purchased from Dr. Weiss.” The Harvard Art Museums did acquire two coins through Weiss’ firm Nomos AG in 2009, both of which appear to have a long provenance. The first, a Drachm of Argos dating to 370-350 BC, can be traced back to an 1886 auction. The second, a fragment of a dekadrachm of Athens dated to 470 BC – 460 BC, is seen in a 1968 edition of Revue Numismatique. (No images are available.) In addition, a gold wreath was loaned for exhibition by Drs. Yvonne and Arnold-Peter Weiss to the Harvard Art Museums from 2008–2010. No additional information was provided about the wreath.

Harvard UPDATE #2: In response to a follow up question about Weiss’ resignation “in 2012”, Aubin says Weiss resigned from the collections committee on January 9, 2012 — six days after his arrest.

*RISD UPDATE: Donna Desrochers, the director of marketing at RISD’s art museum, noted that Weiss’ online bio is out of date: His term as chairman of the board ended last June, and he no longer sits on the museum’s board. In addition, the Syracuse Decadrachm we listed above was not donated by Dr. Weiss. We’ve corrected the post according, and look forward to additional information from RISD.

ALSO: Paul Barford at his Portable Antiquities Collecting blog reports an unconfirmed rumor on coin discussion groups that Interpol arrest warrants may have been issued for an American dealer and two Italian dealers. He has additional thoughts and information here, here and here.

ALSO: David Gill at Looting Matters digs up this quote from Weiss from a 2002 NYT story: “They [ancient coins] have good rates of return — not as good as when we were riding the Internet bubble, but the coin market hasn’t burst.”