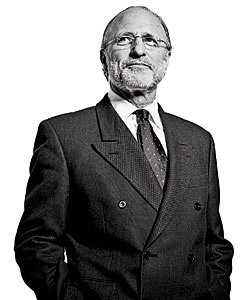

The investigation of antiquities dealer Subhash Kapoor, which made international headlines this week when federal agents raided his Manhattan warehouse, promises to shine a bright light on the illicit trade in antiquities smuggled out of India and other South Asian countries — and the dealer’s ties to prominent museums around the world.

New York authorities issued an arrest warrant for Kapoor, the longtime owner of Madison Avenue gallery Art of the Past, the same day that agents with Immigration and Custom’s Enforcement seized what they said were $20 million worth of stolen Indian artifacts from his Manhattan storage facilities. The seized objects include three Chola period statues that investigators say match objects in Interpol’s database of stolen works of art. Some objects were imported into the U.S. labelled “Marble Garden Table Sets.” An additional $10 million in antiquities were quietly seized from Kapoor in January of this year.

The seized objects are likely the tip of the iceberg of the dealer’s inventory. Since 1974, Kapoor has traded in ancient art from India, Afghanistan, Southeast Asia and the Islamic world, as well as more recent art from India. A sample of his recent inventory can been seen in this 2011 catalog for Art of the Past.

Kapoor’s legal troubles extend far beyond New York. He was detained in Germany in October 2011 and this month extradited to Chennai, India, where he is facing criminal charges of being the mastermind of an idol smuggling ring that plundered ancient temples in Tamil Nadu. Kapoor has reportedly admitted to Indian police that he earned more than $11 million through the transport and sale of plundered Indian antiquities with his daughter and brother through a US corporation called Nimbus International.

Kapoor’s legal troubles extend far beyond New York. He was detained in Germany in October 2011 and this month extradited to Chennai, India, where he is facing criminal charges of being the mastermind of an idol smuggling ring that plundered ancient temples in Tamil Nadu. Kapoor has reportedly admitted to Indian police that he earned more than $11 million through the transport and sale of plundered Indian antiquities with his daughter and brother through a US corporation called Nimbus International.

Kapoor’s New York attorney Christopher Kane did not return a call to his cell phone on Sunday, but told the New York Post that Kapoor ““thinks of himself as a legitimate businessman, and I have no reason to think he’s not.” We’ll post any response we receive here.

As Kapoor’s legal case plays out in India, the spotlight now turns to the dozens of museums and collectors who did business with the dealer. Kapoor boasts in his bio that he has sold antiquities to a long list of leading museums, including The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City; Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Washington D.C.; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, San Francisco; The Art Institute, Chicago; Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond; Musée des Arts Asiatiques-Guimet, Paris; Museum fűr Indische Kunst, Berlin; The National Gallery of Australia, Canberra; Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto; and the Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore.

Investigators have tied a Dancing Shiva at Australia’s National Gallery to Kapoor, the New York Post reported.

In a press release, American investigators asked Kapoor’s clients to check their collections and be in touch. “Some of the artifacts seized during this investigation — which are stolen — have been displayed in major international museums worldwide,” ICE’s Homeland Security Investigations team said in a press release. “Other pieces that match those listed as stolen are still openly on display in some museums. HSI will aggressively pursue the illicit pieces not yet recovered.”

The press, however, is not waiting for museums to come clean. The New York Times queried several museums last week about Kapoor objects in their collections. And on Saturday, The New York Post reported that a statue of Shiva as the Lord of Dance at the National Gallery of Australia has been tied to the investigation.

Not all museums that did business with Kapoor will be in trouble, of course. The Freer-Sackler Gallery, for example, told the New York Times that the only object they had acquired from Kapoor was a 20th century Indian necklace. The two objects in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts’s online catalog linked to Kapoor Galleries, operated by Kapoor’s brother Ramesh, are 17th century Indian paintings.

The Met’s response to the Kapoor investigation has been rather cavalier. Despite the admonition from the federal authorities, the museum will not review its Kapoor antiquities, Holzer told the Times, noting that the collection had long been posted on the Met’s website. One might think that recent history would have taught Met officials time and again that open possession of allegedly stolen property is no protection from claims both legal and moral.

The Met tried to deflect the questions from the press, telling the NY Times that most of the 81 pieces they had acquired from Kapoor were drawings from the 17th, 18th or 19th century highlighted in the 2009 Met exhibit, Living Line: Selected Indian Drawings From the Subhash Kapoor Gift. “They do not appear to be the type of items that they are worried about,” said museum spokesman Harold Holzer.

But a search of the Met’s online catalog reveals several antiquities from Kapoor that authorities likely will be interested in — none have documented ownership histories dating to 1972, when India began controlling exports of ancient art.

Curiously, the Met also has five stone sculptures from Kapoor in its study collection, here and here, for example. They resemble ancient pieces but are labeled by the museum as “20th Century.” All were acquired in 1991. Did the museum acquire these objects from Kapoor, only to discover they were modern forgeries? We’ve asked Holzer for more information.

UPDATE: Harold Holzer tells us, “The group of 20th-century forgeries was accepted as a gift along with the other Kapoor gifts for our study collection, and always identified as such.”

To be fair to the Met, their online collection is far more transparent than that of several other American museums tied to Kapoor. The Toledo Museum of Art told the NY Times that it had received a gift of 44 terracotta antiquities from Kapoor in 2007. The only object that appears in a search of the museum’s online collection is a terracotta vessel purchased in 2008. The museum published the object in 2009 in a book of the museum’s masterworks, but offers no ownership history other than saying it was created in Chandraketugarh, an archaeological site north-east of Kolkata. Where was it before Toledo? What are the ownership histories for the other 43 objects acquired from Kapoor?

To be fair to the Met, their online collection is far more transparent than that of several other American museums tied to Kapoor. The Toledo Museum of Art told the NY Times that it had received a gift of 44 terracotta antiquities from Kapoor in 2007. The only object that appears in a search of the museum’s online collection is a terracotta vessel purchased in 2008. The museum published the object in 2009 in a book of the museum’s masterworks, but offers no ownership history other than saying it was created in Chandraketugarh, an archaeological site north-east of Kolkata. Where was it before Toledo? What are the ownership histories for the other 43 objects acquired from Kapoor?

We’ve asked the Toledo Museum for that information, but apparently such requests are a low priority there. More than a month ago, we requested information about objects in their collection tied to two other dealers who investigators have connected to the illicit trade — Edoardo Almagia and Gianfranco Becchina. We have still not received a response.

Several years ago, the Getty Museum took a similar stance when faced with questions about objects in their collection. Stonewalling only convinced the public of the museum’s bad faith, and fueled the zeal of investigations by foreign governments and the media. Museums would be smart to heed those lessons from the Getty case, lest they relive the consequences.

Like the Almagia investigation, the Kapoor case will be a test for how transparent American museums can be in the face of unpleasant questions about ancient art in their collections. Will they take a proactive approach to investigating their collections, as they have done with objects with unclear provenance from World War II era? Or will they stonewall and encourage others to do the investigation for them?

Hat-Tips: Several people have been covering the Kapoor case for months, and you should read their detailed coverage. The Indian press, especially the Times of India, has been covering the case for months. Damien Huffer, whose excellent blog It Surfaced Down Under tracks the illicit antiquities trade in the Southern Hemisphere, was one of the first to pick up the story, a distinction that earned him repeated legal threats. Paul Barford’s blog has also diligently tracked reports on the case, adding his salty commentary along the way. Most recently, The New York Post broke the news of the Manhattan raids last week and has followed-up with some additional scoops.

UPDATE: Attorney Rick St. Hiliare has some very interesting thoughts on what the Kapoor case reveals about antiquities smuggling networks: “Examining the import and export methods surrounding the Kapoor case not only can aid police in the United States and India in their current investigations targeting the alleged idol thief, but it can help policymakers, criminologists, and scholars think about better ways to detect, uncover, interdict, and prosecute future crimes of heritage trafficking.” Hilaire also offers excellent analysis of the bills of lading allegedly used by Kapoor’s enterprises, revealing how these objects were able to enter the U.S. under false premises. He goes on to say the case might give a boost to our WikiLoot project, which is designed to suss out these very matters. Worth reading his entire post.

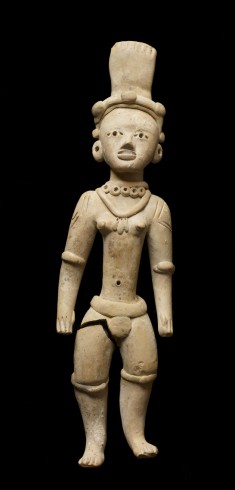

First, there are the fakes. To its credit, the Walters is completely up front about the fact that some pieces in the Bourne collection are probably not what they claim to be. “[T]he atypical imagery of these objects calls into question their authenticity,” says the wall label next to a pair of Maya eccentric flints. It adds, helpfully, that tests are inconclusive “because modern replicas are made using the same kinds of tools and techniques as well as the same sources of flint” as the real ones. So, in this case, we’re learning more about technique for making fakes than about Maya flints.

First, there are the fakes. To its credit, the Walters is completely up front about the fact that some pieces in the Bourne collection are probably not what they claim to be. “[T]he atypical imagery of these objects calls into question their authenticity,” says the wall label next to a pair of Maya eccentric flints. It adds, helpfully, that tests are inconclusive “because modern replicas are made using the same kinds of tools and techniques as well as the same sources of flint” as the real ones. So, in this case, we’re learning more about technique for making fakes than about Maya flints.