UPDATE September 2014: Japanese dealer Noriyoshi Horiuchi has agreed to return the sarcophagus lid to Italy in a stipulation reached with the federal government. Rick St. Hilaire has the news here.

UPDATE: After a 13 year legal battle, Switzerland has returned to Italy the last of 4,536 looted objects that were seized from Gianfranco Becchina’s warehouse and gallery in Basel, according to a Swiss media report. (Sources have confirmed the article, which does not name the dealer, refers to Becchina.)

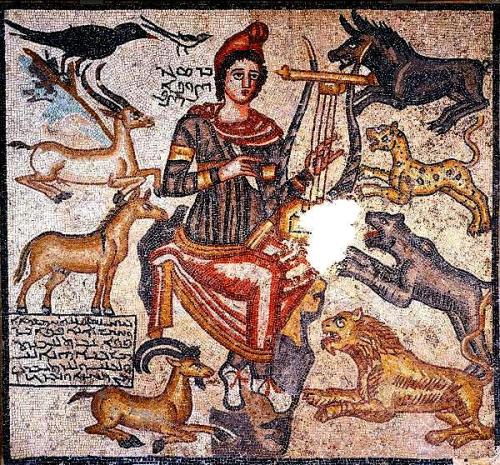

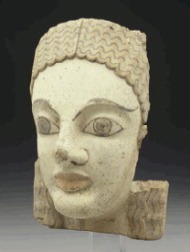

Federal authorities seized a $4 million Roman sarcophagus lid from a New York warehouse on Friday, alleging it had been looted, smuggled out of Italy and sold to convicted Italian antiquities trafficker Gianfranco Becchina in the 1980s before passing through a who’s who of the illicit antiquities trade.

The sculpture surfaced again in May 2013, when it was exhibited at the Park Avenue Armory by Phoenix Ancient Art, the antiquities dealership of Hicham and Ali Aboutaam, Lebanese brothers who have both been convicted of crimes related to trafficking in looted art. The Aboutaam’s lawyer told the New York Times that they had exhibited the sculpture on behalf of a client and played no role in its shipping or importation.

The sculpture surfaced again in May 2013, when it was exhibited at the Park Avenue Armory by Phoenix Ancient Art, the antiquities dealership of Hicham and Ali Aboutaam, Lebanese brothers who have both been convicted of crimes related to trafficking in looted art. The Aboutaam’s lawyer told the New York Times that they had exhibited the sculpture on behalf of a client and played no role in its shipping or importation.

The Aboutaams would not identify their client. Records show that the sculpture was in the possession of Noriyoshi Horiuchi, a Japanese antiquities dealer with close ties to Becchina. Horiuchi was instrumental in building the antiquities collection at the Miho Museum and returned more than 300 looted antiquities to Italy after a 2008 raid on his Geneva warehouse.

UPDATE: Phoenix has confirmed to another journalist that their “client” was Horiuchi, who had been asking $3 million for the sarcophagus. The gallery claims to have conducted “comprehensive due diligence” on the sarcophagus tracing it back 30 years but did not learn that it had belonged to Ortiz and Becchina.

The seizure of the Sleeping Beauty was possible with the help of Italian investigators and their access to the Becchina Dossier — the dealer’s archive of business records and photographs documenting his several decades in the illicit antiquities trade.

The Becchina archive’s 140 binders contain more than 13,000 documents — shipping records, invoices and thousands of Polaroid images showing recently looted artifacts, including the Sleeping Beauty. It was seized in 2002 by Italian and Swiss authorities during a raid on Becchina’s Basel warehouse and gallery Palladion Antique Kunst. In 2011, Italy convicted Becchina of being a key middleman in the illicit antiquities trade. He has appealed that conviction, but the seizure of his archives was upheld by Italy’s high court in February 2012.

The Becchina archive’s 140 binders contain more than 13,000 documents — shipping records, invoices and thousands of Polaroid images showing recently looted artifacts, including the Sleeping Beauty. It was seized in 2002 by Italian and Swiss authorities during a raid on Becchina’s Basel warehouse and gallery Palladion Antique Kunst. In 2011, Italy convicted Becchina of being a key middleman in the illicit antiquities trade. He has appealed that conviction, but the seizure of his archives was upheld by Italy’s high court in February 2012.

UPDATE: Gianfranco Becchina has released the following statement on the sarcophagus to RAI, Italy’s national public broadcaster (translated from Italian via Google): “It ‘s true that, several decades ago, the work belonged to the Gallery Palladion Antike Kunst in Basel which was the owner. Contrary to the contention of the news, the sculpture has come to me later a regular exchange transaction as evidenced by the bubble of Swiss Customs reproduced in the service of the New York Times, from which, to all evidence , information in your possession are inspired. The assertion that want to work from a theft is absolutely bizarre and devoid of any support, documentary or otherwise, of such an assumption. The transaction took place in a country, which is Switzerland, where the trade findings was totally legitimate and not subject to any restrictions except the payment of customs duties on imports. According to information provided to me by the seller , the artifact had landed in Italy from Tunisia. The assertion of my conviction relating to other events linked to the art trade, is blatantly false: no hearing has taken place, let alone have been condemned. But this is another story!”

Becchina’s archive is far more detailed that that of his more famous rival, Giacamo Medici, whose collection of Polaroid photographs sparked an international scandal and forced the return of more than 100 prized antiquities on display at American museums. As the case of the Sleeping Beauty illustrates, the Becchina Dossier provides an unprecedented roadmap of the illicit trade of Greek and Roman material looted from Italy and beyond.

A Winding Path Through the Illicit Trade

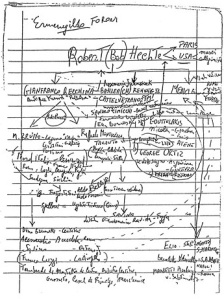

Records from Becchina’s archive show the looted sarcophagus was first offered to Becchina by Antonio “Nino” Savoca, an Italian dealer with a shop in Munich who acquired it from looters along with a cache of other large marbles. Savoca sent Becchina a series of Polaroids showing the sarcophagus lid in two fragments. In the image below, you can see the bottom half of the sculpture showing the Beauty’s knees and feet.

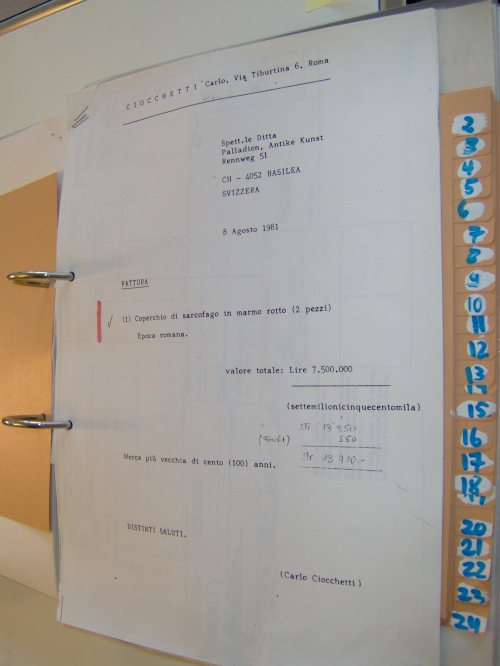

A receipt dated 8/8/81 shows Becchina bought it for 7.5 million lire from Carlo Ciochetti, a frontman for Savoca in Rome.

A receipt dated 8/8/81 shows Becchina bought it for 7.5 million lire from Carlo Ciochetti, a frontman for Savoca in Rome.

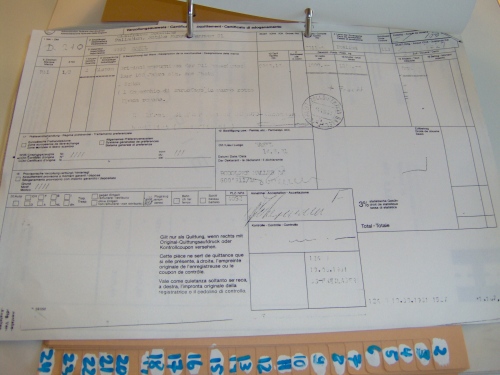

A Swiss customs form dated 8.14.81 shows Becchina imported the sarcophagus to Basel, where it was accepted by his shipping agent Rodolphe Haller.

A receipt dated 9/15/81 shows Becchina sold the fanciulla,or maiden, to Swiss antiquities collector/dealer George Ortiz for Fr. 80,000. Sources say that in fact Ortiz provided the financing for Becchina’s purchase of the sarcophagus and the two owned it jointly for several years.

An image attached to the Ortiz receipt shows the sarcophagus as it appeared before restoration.

In 1982, the sarcophagus was offered for sale to the Getty Museum, which turned it down, sources say. It was also exhibited at a the Historical Museum of Bern for several months during late 1982 and early 1983 and published in a German catalog.

A list written in German and dated July 15 1986 describes “a broken sarcophagus ex Ciochetti” as the first of 24 objects jointly owned by Becchina and Ortiz. Many of the objects on the list are the same as those recently looted objects shown in the Savoca Polaroids.

It is not clear what happened to the sarcophagus after 1986. At some point it was extensively restored, with the missing marble fragment at the break-point filled in, and acquired by Horiuchi, the Japanese dealer known to have worked closely with Becchina. When and how it was imported into the Unites States is still under investigation.

It is not clear what happened to the sarcophagus after 1986. At some point it was extensively restored, with the missing marble fragment at the break-point filled in, and acquired by Horiuchi, the Japanese dealer known to have worked closely with Becchina. When and how it was imported into the Unites States is still under investigation.

This is the condition it was found in when federal agents discovered it in the warehouse in Long Island City, New York.

And here are images of the Sleeping Beauty’s seizure today, courtesy of ICE and Tony Aiello, a reporter at CBS New York.

The Sleeping Beauty will be returned to Italy soon, officials said. “Whether looted cultural property enters our ports today or decades ago, it is our responsibility to see that it is returned to its rightful owners, in this case, the Italian people,” stated U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of New York Loretta Lynch. “We will continue to use all legal tools available to us to seize, forfeit and repatriate stolen cultural property.”

Meanwhile, thousands of other sleeping beauties whose origins are detailed in the Becchina archive remain to be found. More on those soon…