An exciting new research effort has been launched by some of the most prominent researchers of the illicit antiquities trade.

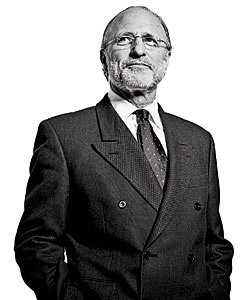

Simon Mackenzie, Neil Brodie, Suzie Thomas and Donna Yates* at the University of Glasgow have received £1 million over four years from the European Research Council to pursue new research of the illicit trade in ancient art.

The program, called “Global Traffic in Cultural Objects,” will be based at Glasgow’s Scottish Centre for Crime and Justice Research. Here’s how the team describes their goal:

“National and international laws intended to regulate or suppress the trade have been only partially successful, and the illicit trade has been linked to further criminal problems such as corruption and physical violence…By developing new empirical approaches and drawing upon criminological theory, this project will work towards a regulatory regime that goes beyond straightforward law enforcement, allowing the legitimate exchange of cultural objects while suppressing the illicit market.”

The project’s four main endeavors are:

1. Mapping and measurement. Through a series of case studies, the project will examine publicly available sales data to establish whether they can be used to estimate flows of illicit material through the market, and therefore to assess the effectiveness of any implemented regulation.

2. Qualitative data-gathering and analysis. Through ethnographic interviews of market agents such as dealers, collectors, museum curators and university academics, the project will gather information about the trade in licit and illicit cultural objects, and opinions about suitable regulation and opportunities for novel regulatory interventions. It will also, by means of a major case study, trace the path taken by a defined category of illicit material from ground to market, thereby offering greater depth to the analysis.

3. Regulation theory and practice. There will be a comprehensive review of the academic and policy literature as regards comparable transnational criminal markets and their regulation. Regulatory successes and failures will be identified, and considered in relation to the traffic in cultural objects, utilizing information obtained through themes 1 and 2. The project will also consider whether the traffic in cultural objects is ‘knotted’ together with other criminal activities in such a way as to render it insoluble as an isolated problem.

4. Knowledge mobilization. The project will establish a website that will make available project outputs and data, and that will also contain an ‘encyclopedia’ of material relevant to the project and to the traffic in cultural objects more generally.

We recently interviewed Simon Mackenzie, a criminologist who has been studying the antiquities trade since 2002, about his perspective on the illicit antiquities trade. (We’ve edited a bit for clarity and length.)

Chasing Aphrodite: What is known and not known about the illicit antiquities trade? How does our knowledge of it compare with our knowledge of other types of crime?

People are always talking about the illicit antiquities trade as something that is under-researched, with a small number of people working in the field. But when you think about it, it’s not too bad. Clemency Coggins really started the field in the 1960s. The last 40 years, from UNESCO onwards, has been a period of relatively high activity compared to other criminal problems – quite a lot has happened. There’s been increasing regulation of museums and ethical codes adopted. Once you start looking into the literature — for example, ethnographic studies of markets by Morag Kersel , the work of Christopher Chippindale and David Gill, Ricardo Elia, Patty Gerstenblith. It has been a small field, but there are a good spread of methodological approaches, with respectable and reliable researchers.

CA: Estimates of the size of illicit trade range from tens of millions to as much as $2 billion annually. Why?

CA: Is organized crime involved in antiquities trade?

SM: There is clearly organized crime in the antiquities market, as we conventionally conceive of organized crime. The more interesting question is whether antiquities trafficking is in itself an organized crime. It’s not what we would think of as organized crime on its face because the actors are often quite respectable figures. It seems counter-intuitive to say that museums and auction houses are organized crime. But look at the definition of organized crime: three or more people operating over a sustained period of time in a serious criminal way. Antiquities trafficking meets that definition. So you can make a technical argument quite easily.

The more interesting question to ask is: why do we care whether it’s organized crime? The policy response to organized crime, the regulatory response, is much greater, more of an international threat. So the distinction can be quite important on a policy basis.

The reason why organized criminals are involved in the antiquities trade is because it’s under-regulated. But you can take the organized criminal out of the antiquities trade and you’ll still have looting. It’s a story of supply and demand on an international basis. The trade attracts organized criminals, but they don’t define the shape of it because it is created and sustained by more conventional trade actors.

CA: The trade in illicit antiquities is often seen, especially in the United States, as a victimless crime. The public sometimes has trouble grasping the harm. Your thoughts?

SM: It’s difficult. The general public is not particularly interested in the context of any particular object dug up in a far flung corner of the world. And yet, museums and cultural debates are a strong current full of voices who feel very strongly about people’s culture and human rights. So in one sense, it’s certainly true that sometimes people don’t get that broken old pots are important to mankind. But when you elevate that to a greater concern with history and culture and knowledge and civilization, what that means and how we might find our way forward, people do care quite deeply about that. These are fundamentals.

CA: What do you think of the current regulatory regimes for the antiquities trade? Your thoughts on de-criminalization?

SM: Most criminologists agree that supply-side interventions are going to be problematic, particularly on their own. The drug trade and prohibition are pretty good examples of trying to control something where there’s a high level of demand in a globalized economy. None of these have particularly good records of success. Most of the current ideas seems to be about reducing demand or, alternatively, taking an end-to-end type solution — take both ends seriously and start to unwind the economic cultural and social forces underpinning the market. Once you see that, strict legal responses begin to look problematic. It’s very difficult for the law to seriously engage with an entrenched, large-scale global trade. The nature of regulatory intervention in the cultural heritage market has largely been legal. Mostly its been about UNESCO, passing laws in source countries, prohibition of theft, and passing laws in market countries to prevent purchase. The interesting question for regulation is how do we build up systems around these laws we have.

Some scholars, such as Paul Bator, have argued that increasing regulation produces the black-markets — that regulators are culpable for the illicit trade. I’ve never really bought into that. It’s a dead end: if you believe that, what do you do, stand back? You can talk about decriminalizing cannabis use, where the moral limitations are so widely disputed so there’s a general debate about whether it should be a crime. But not many people would seriously argue that knowingly steeling cultural property is ok. It’s reasonably clear that all sides say it’s wrong. Therefore the idea that we should decriminalize it doesn’t seem to do much except legitimate illicit stuff. It wouldn’t stop the illicit trade. It might make it worse.

*UPDATE: We’ve added Donna Yates, who recently joined the Glasgow team fresh from her PhD work at Cambridge.

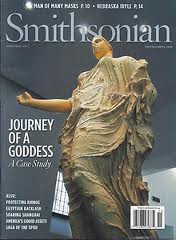

First, there are the fakes. To its credit, the Walters is completely up front about the fact that some pieces in the Bourne collection are probably not what they claim to be. “[T]he atypical imagery of these objects calls into question their authenticity,” says the wall label next to a pair of Maya eccentric flints. It adds, helpfully, that tests are inconclusive “because modern replicas are made using the same kinds of tools and techniques as well as the same sources of flint” as the real ones. So, in this case, we’re learning more about technique for making fakes than about Maya flints.

First, there are the fakes. To its credit, the Walters is completely up front about the fact that some pieces in the Bourne collection are probably not what they claim to be. “[T]he atypical imagery of these objects calls into question their authenticity,” says the wall label next to a pair of Maya eccentric flints. It adds, helpfully, that tests are inconclusive “because modern replicas are made using the same kinds of tools and techniques as well as the same sources of flint” as the real ones. So, in this case, we’re learning more about technique for making fakes than about Maya flints.