We’re continuing to trace suspect Cambodian antiquities linked to Douglas Latchford, the man at the center of the on-going federal looting probe that we’ve detailed in previous posts here. Last week we wrote about suspect Khmer antiquities at the Denver Art Museum. Here are our latest finds:

The Kimbell Art Museum

In 1988, the Kimbell Art Museum purchased an important 7th century Khmer sculpture from Latchford.

At the time of purchase, the statue had no documented ownership history. The only record the Kimbell obtained about its origins was a signed guarantee from Latchford claiming the statue had been in his possession in Thailand since 1968 and had legally been shipped to the UK in 1987, a museum spokeswoman said.

Latchford has made similar claims about contested Khmer statues at Sotheby’s and the Norton Simon Museum that are now the focus on a federal lawsuit. Federal investigators have alleged in court filings that Latchford purchased those statues after they were looted in the early 1970s and smuggled to Thailand, a claim Latchford denies. (See our previous coverage of the case here.)

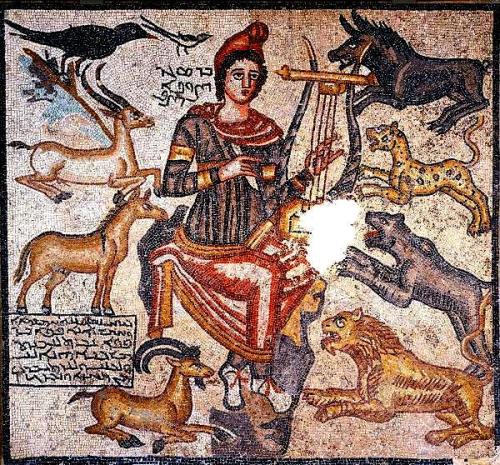

The statue represents Harihara, a Hindu deity that combined the destructive force of Shiva and the creative power of Vishnu. The statue’s style suggests the piece came from the pre-Angkor ruins of Prasat Andet, in central Cambodia. The Kimbell has no evidence of legal export from Cambodian, a museum spokeswoman confirmed.

Acquiring an object based exclusively on a dealer’s warranty — rather than an actual documented ownership history that proves it was not looted — was a common tactic in the 1980s, particularly for pieces that were likely looted. As we described in Chasing Aphrodite, the J. Paul Getty Museum passed a new acquisition policy for antiquities in 1987 that called for a dealer warranty in place of an inquiry into an object’s origins. The practice allowed the Getty to continue acquiring objects it knew or suspected had been looted — including an $18 million statue of Aphrodite — while providing a modicum of legal and public relations cover if the statue were later questioned. But the policy failed: The Getty returned the Aphrodite to Italy in 2010 after our investigation in the LA Times made clear the dealer warranty was a thin cover for the truth — the statue had been looted from an archaeological site in central Sicily.

Acquiring an object based exclusively on a dealer’s warranty — rather than an actual documented ownership history that proves it was not looted — was a common tactic in the 1980s, particularly for pieces that were likely looted. As we described in Chasing Aphrodite, the J. Paul Getty Museum passed a new acquisition policy for antiquities in 1987 that called for a dealer warranty in place of an inquiry into an object’s origins. The practice allowed the Getty to continue acquiring objects it knew or suspected had been looted — including an $18 million statue of Aphrodite — while providing a modicum of legal and public relations cover if the statue were later questioned. But the policy failed: The Getty returned the Aphrodite to Italy in 2010 after our investigation in the LA Times made clear the dealer warranty was a thin cover for the truth — the statue had been looted from an archaeological site in central Sicily.

The Kimbell believes the Harihara is the only object in its collection with ties to Latchford, but can’t be certain, a museum spokeswoman said. It is not the only suspect piece of ancient art to surface at the museum. In February, we wrote about the Kimbell’s 5th century BC Greek cup by the Douris painter. After we noted the cup’s ownership history had been traced to Elie Borowski, a dealer who has been linked to the illicit trade in Classical antiquities, the Kimbell announced it would publish the cup on a registry of objects maintained by the Association of Art Museum Directors. The cup was never listed in the registry — likely because it was acquired prior to 2008, when the directors group began requiring suspect antiquities to be posted. (This leaves the question: where should suspect antiquities acquired before 2008 be posted publicly to encourage further provenance research? Museums should be publishing the complete known provenance of all their antiquities, but don’t. We’ve proposed our own answer.)

The Kimbell believes the Harihara is the only object in its collection with ties to Latchford, but can’t be certain, a museum spokeswoman said. It is not the only suspect piece of ancient art to surface at the museum. In February, we wrote about the Kimbell’s 5th century BC Greek cup by the Douris painter. After we noted the cup’s ownership history had been traced to Elie Borowski, a dealer who has been linked to the illicit trade in Classical antiquities, the Kimbell announced it would publish the cup on a registry of objects maintained by the Association of Art Museum Directors. The cup was never listed in the registry — likely because it was acquired prior to 2008, when the directors group began requiring suspect antiquities to be posted. (This leaves the question: where should suspect antiquities acquired before 2008 be posted publicly to encourage further provenance research? Museums should be publishing the complete known provenance of all their antiquities, but don’t. We’ve proposed our own answer.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

While researching the Kimbell’s Harihara, we noticed that The Metropolitan Museum of Art purchased a similar Harihara, also linked to Prasat Andet, in 1977. We’ve asked the Met for the provenance of the statue, as none is listed on their website.

While researching the Kimbell’s Harihara, we noticed that The Metropolitan Museum of Art purchased a similar Harihara, also linked to Prasat Andet, in 1977. We’ve asked the Met for the provenance of the statue, as none is listed on their website.

The Met also has several pieces from Latchford. The New York Times has previously noted that Cambodia will ask the museum to return its two prominently displayed Standing Attendants, which also came through Latchford from Koh Ker. As Paul Barford has noted, the knees of those statues bear clear signs of having been hacked from a base by looters. (The Met’s high resolution photos and zoom tool are quite useful here.)

David Gill has also noted that the statues came to the museum in fragments from different sources acquired over several years and were reassembled at the Met. Martin Lerner, the Met’s former Asian Art curator, noted the happy coincidence in the catalog: “It is particularly gratifying that the monumental bodies join up with heads already in the collection.” This appears similar to a pattern we’ve seen in objects passed through smuggling networks that dealt in Classical antiquities, the so-called “fragments game” identified by Italian investigators and noted by Gill here.

Gill has also helpfully identified several other Latchford donations at the Met:

A 10th century Khmer Head of Buddha acquired in 1983 as a gift from Latchford. (1983.551)

A 10th century Khmer Head of Buddha acquired in 1983 as a gift from Latchford. (1983.551)

A 12th century Bodhisattva from Nepal acquired in 1989 as a gift from Spink & Son Ltd. and Douglas A. J. Latchford. (1989.237.1)

A bronze 9th century Bodhisattva Maitreya from Thailand acquired in 1989 as a gift from Spink & Son Ltd. and Douglas A. J. Latchford. (1989.237.2)

A 2nd century Ghandaran plaque from Pakistan acquired as gift of Spink & Son Ltd. and Douglas A. J. Latchford in 1989. (1989.237.3)

The gifts suggest several things: Latchford was a generous donor to the Met over several years, and dealt not just in Khmer art but also material from South Asia. It would be worth perusing the Met’s 1994 catalog of Asian Art for other examples of material from South East Asia. For example, given the history of looting at Koh Ker, we were interested in how this gilt bronze statue of a king from Kor Ker (left) ended up in the collection Walter Annenberg before being acquired by the Met in 1988.

The gifts suggest several things: Latchford was a generous donor to the Met over several years, and dealt not just in Khmer art but also material from South Asia. It would be worth perusing the Met’s 1994 catalog of Asian Art for other examples of material from South East Asia. For example, given the history of looting at Koh Ker, we were interested in how this gilt bronze statue of a king from Kor Ker (left) ended up in the collection Walter Annenberg before being acquired by the Met in 1988.

We’ll continue looking for Latchford objects in other museums. If you’ve got any tips, drop us at line at ChasingAphrodite@gmail.com

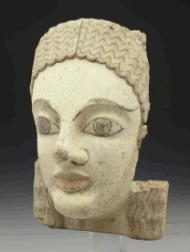

3. Sun God (Surya) from Cambodia or Vietnam. 600’s to 700’s, Pre-Angkor period, sandstone. Purchased from Latchford in 2004. Accession #2004.371. Published in “Adoration and Glory.” No other provenance information was provided.

3. Sun God (Surya) from Cambodia or Vietnam. 600’s to 700’s, Pre-Angkor period, sandstone. Purchased from Latchford in 2004. Accession #2004.371. Published in “Adoration and Glory.” No other provenance information was provided.

Hab Touch: The Cambodian government official who Sotheby’s debated notifying before the statue’s sale. (see Exhibit 10) Dismissed as a “bureaucrat,” Touch ultimately objected to the statue’s sale and asked for its return to Cambodia.

Hab Touch: The Cambodian government official who Sotheby’s debated notifying before the statue’s sale. (see Exhibit 10) Dismissed as a “bureaucrat,” Touch ultimately objected to the statue’s sale and asked for its return to Cambodia.

“In our view, Mr Kapoor is one of the most prolific commodities smugglers in the world,” said Immigration and Customs Enforcement Special Agent in Charge James T. Hayes (shown above with the seized objects.) “It’s one of our most significant antiquities and artifacts investigations that we’ve conducted in the history of this agency.”

“In our view, Mr Kapoor is one of the most prolific commodities smugglers in the world,” said Immigration and Customs Enforcement Special Agent in Charge James T. Hayes (shown above with the seized objects.) “It’s one of our most significant antiquities and artifacts investigations that we’ve conducted in the history of this agency.” Hayes stressed that the Kapoor investigation, dubbed Operation Hidden Idol, was on-going as agents continue to dig into Kapoor’s four decades as a Manhattan dealer whose gallery Art of the Past sold objects to museums around the world. Those include some of the

Hayes stressed that the Kapoor investigation, dubbed Operation Hidden Idol, was on-going as agents continue to dig into Kapoor’s four decades as a Manhattan dealer whose gallery Art of the Past sold objects to museums around the world. Those include some of the